Diderot’s Encyclopédie,published between 1751 and 1772, laid the groundwork for new modes of thinking that would flourish in the nineteenth century. Indeed, on both sides of the Atlantic, the 1800s witnessed a voracious appetite for cataloguing, compiling, and understanding every detail of everything. From wunderkammers (or “cabinets of curiousity”) where objects were meticulously displayed for curious eyes to Dmitri Mendeleev’s painstaking 1869 Periodic Law that built the groundwork for the modern Periodic Table, the nineteenth century was filled with a lust for order and understanding of the natural world.

It is this climate of categorization that led phrenology to come into vogue. Though the discipline was invented at the very end of the previous century by Franz Joseph Gall, its character was profoundly rooted in the spirit of the nineteenth century. The first of the two books discovered by the UVa Book Traces team, George Combe’s A System of Phrenology (1838), defines the discipline as follows:

” Phrenology, derived from [the Greek] φρήν (phrēn) mind and λόγος (logos) discourse, professes to be a system of Philosophy of the Human Mind, and…to throw light on the primitive powers of feeling which incite us to action, and the capacities of thinking that guide our exertions…” (Combe 1)

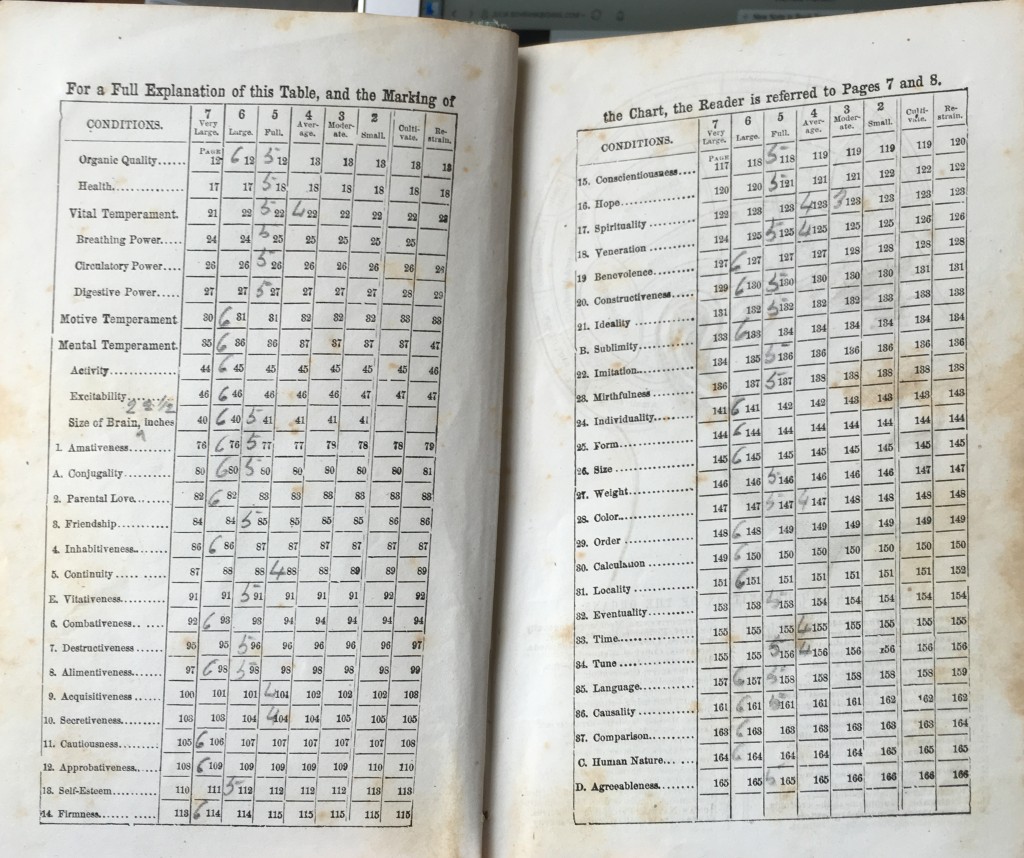

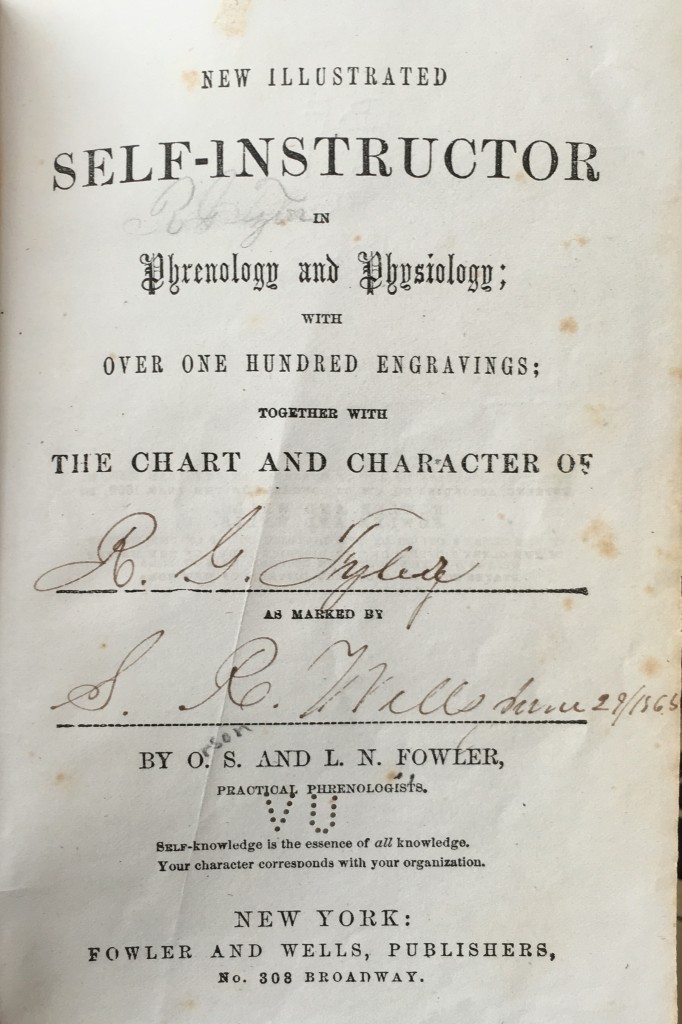

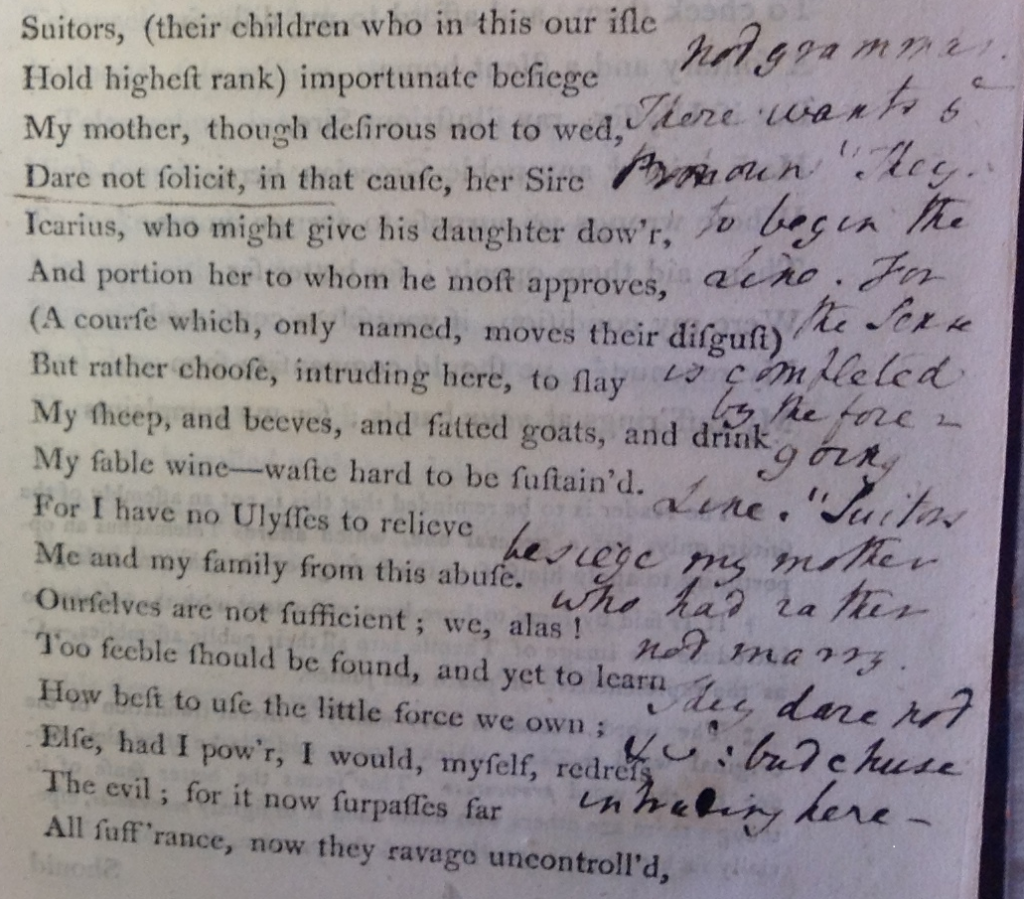

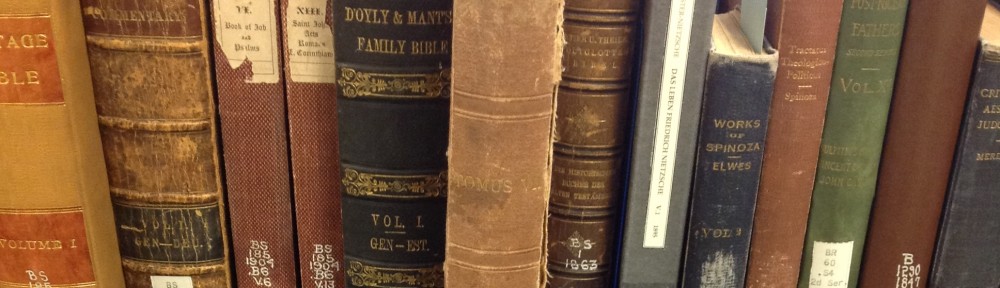

The methodology of this “system” might cause a modern person to raise an eyebrow: Gall and his followers believed that they could gain insight into these “powers of feeling” and “capacities of thinking” by evaluating a person’s skull. The New illustrated self-instructor in phrenology and physiology (1859), the second book in the Book Traces project to address the subject, furnishes a list of nearly forty “organs” — essentially nooks and crannies — of the skull that could reveal traits of its owner:

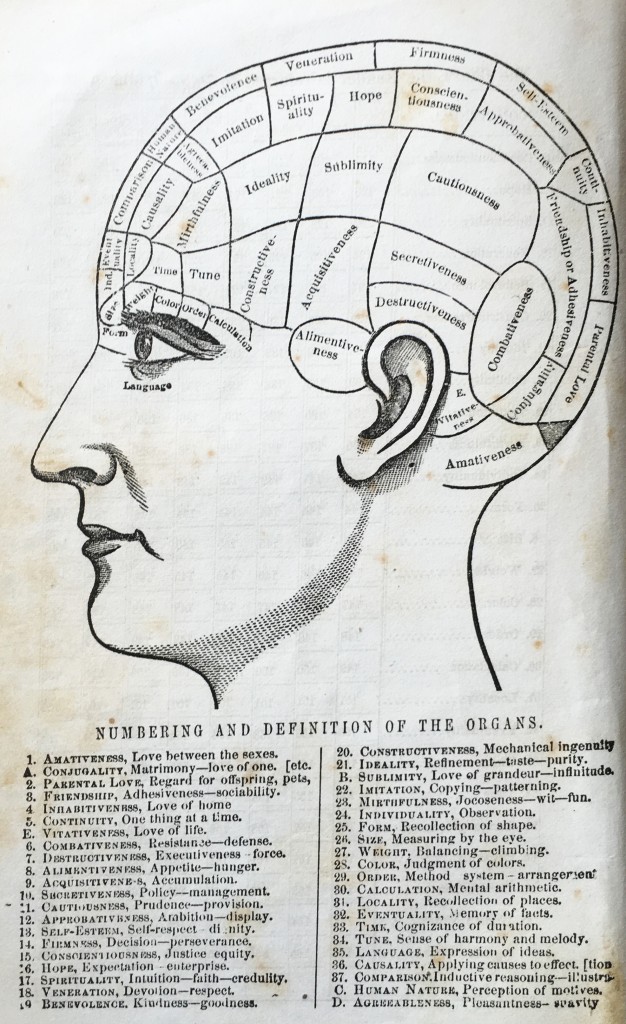

Many of these traits may seem quaint and even humorous. We can imagine such humorous vignettes as a lady feeling a suitor’s scalp for “Conjugality” to see if a man is inevitably a cheater, or a friend palpating above an ear to see if the person has enough “Secretiveness” to be trusted with a spare key. Indeed, O.S. and L.N. Fowler, the earnest authors of the Self-instructor, even furnish us with images that we, using with our modern vocabulary, can find very funny indeed:

“Well, of course that Emerson is an idiot; he looks just like one” we can imagine the Fowlers declaring with nonchalance.

A humorous interpretation of this “idiocy” would, however, require the modern levity with which the word can be used. If we put the word “idiot” back into its temporal (and pejorative) context, it quickly loses its humor. The American Heritage Stedman’s Medical Dictionary provides us with the following historical definition, stipulating that this use is now highly offensive:

idiot id·i·ot (ĭd’ē-ət)

n.

A person of profound mental retardation having a mental age below threeyears and generally being unable to learn connected speech or guard against common dangers.

Following this line of thinking, it becomes fairly easy to see how phrenology, in the wrong hands, could have very dangerous consequences indeed. For example, with Emerson above, we now understand that certain congenital physical traits may also come with life-altering mental traits. It is possible, then, that Emerson’s long forehead and craggy profile are hallmarks of what we might today call a “mental disability” in a medical or governmental setting or a “neurodivergent mind” in a social justice context. It is also possible that Emerson just looks like he does! We could take this phrenological reading of Emerson’s skull as a benevolent (or at least objective) attempt to acknowledge his difference, but given that he is juxtaposed with illustrations of various literary and political notables such as Edgar Allan Poe and George Washington on other pages of the volume, it seems that the authors are identifying him as being a comparatively inferior individual. Furthermore, they are casting him as an “idiot” for something he didn’t choose; he was born looking like this rather than like Poe or Washington and there is little he can do about it.

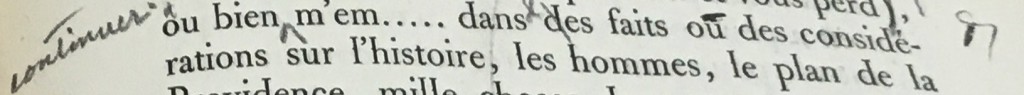

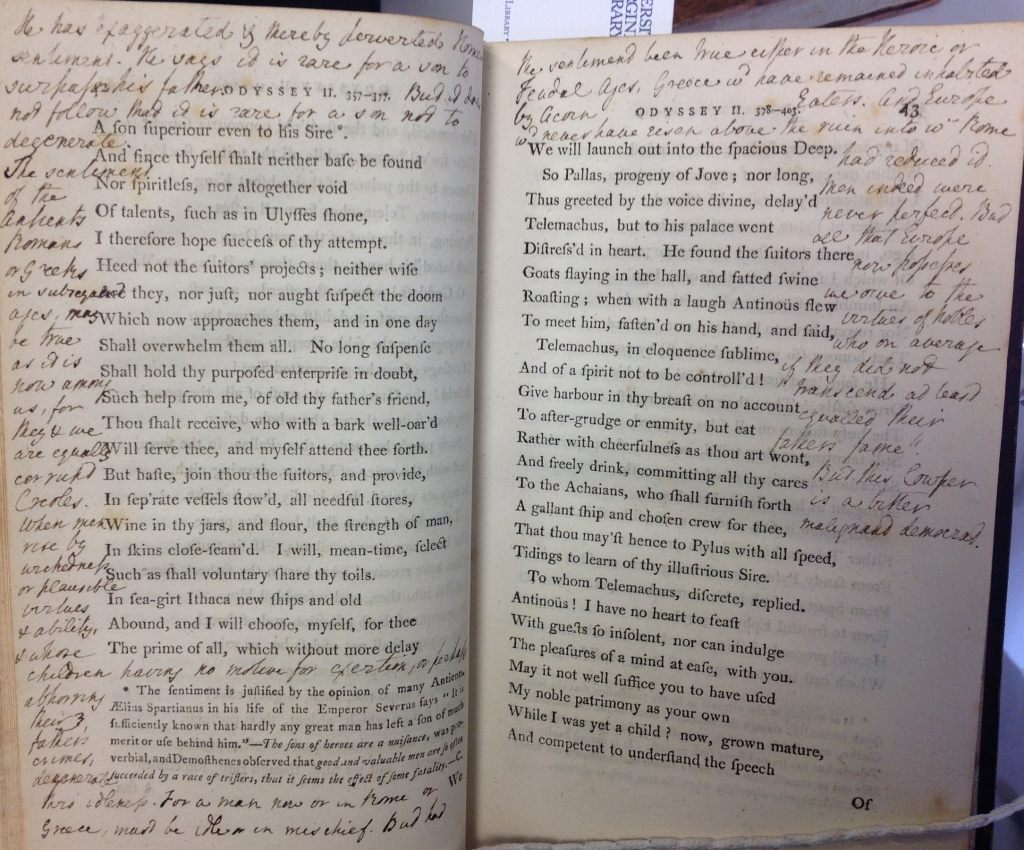

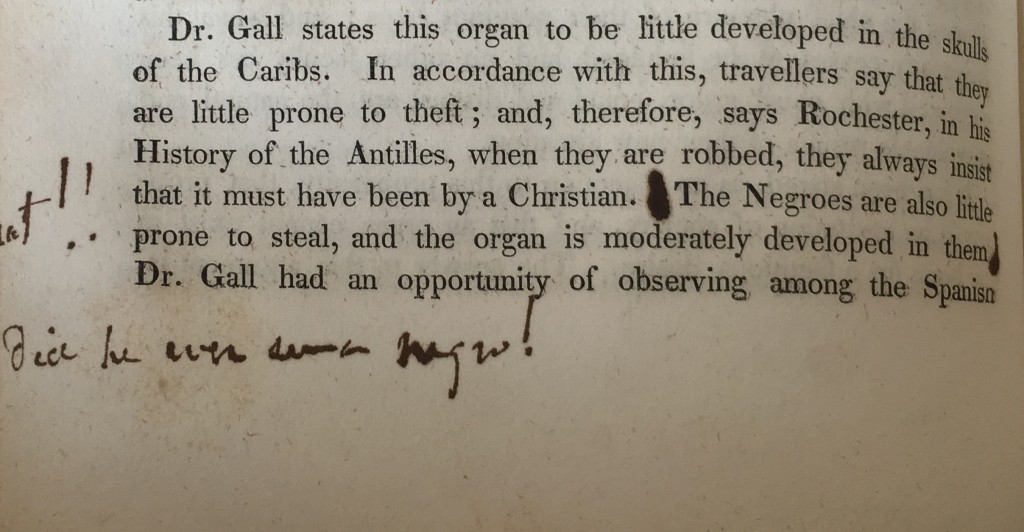

One of the interventions in the Combe text reveals that the discipline of phrenology was also contorted to draw conclusions about race. On page 198, which covers “acquisitiveness,” or the desire to accumulate goods, we see two vast generalizations in action:

The intervention that has been cut off likely reads “What!!” and below the handwritten text appears to read “Did he ever see a negro!”

While Combe, the author of the printed text, makes the positive — yet nonetheless prejudicial— observation that “Negroes are… little prone to steal,” the marginalia reveals a much more pejorative viewpoint. The handwritten text in pen brackets or highlights this observation and makes the observation that Dr. Gall must not have met or observed “a negro,” implying that, in this person’s mind, people of that heritage are indeed prone to stealing.

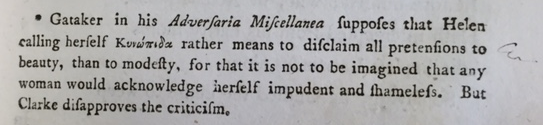

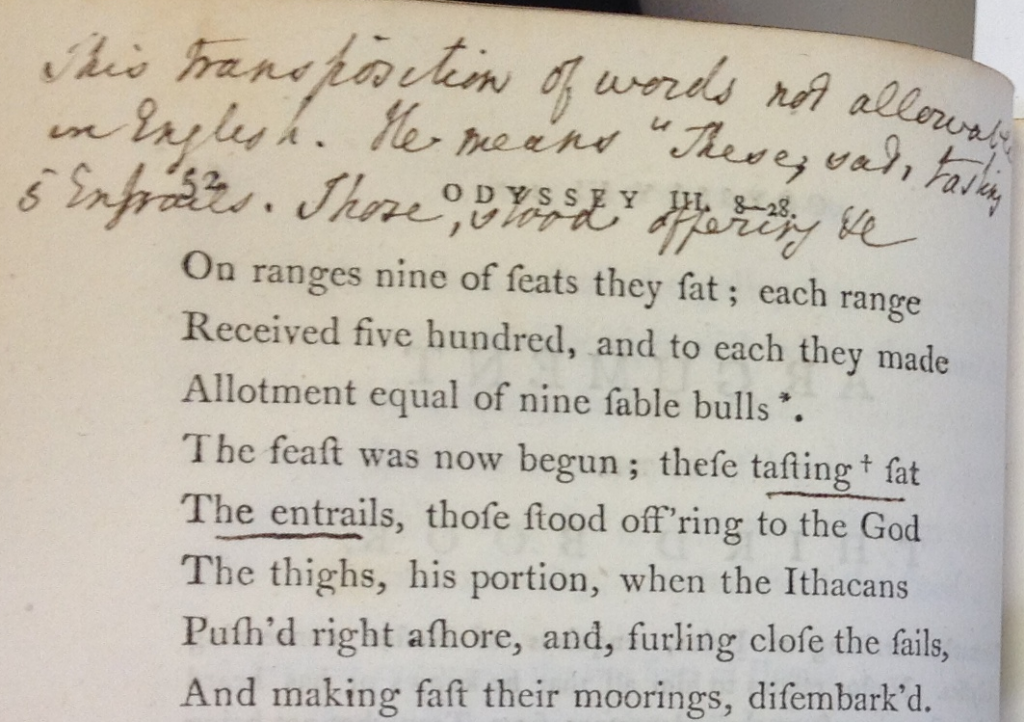

We have no traces of this incredulous reader’s identity, but what we do know about them can help us see how they may have been employing phrenology as a form of confirmation bias. Throughout the text, there are notes “correcting” Combe’s text that, while they employ an elevated vocabulary, are often rife with misspellings and rarely furnish proof. Take, for example, this indignant footer note on page 127, in the chapter on “Concentrativeness”:

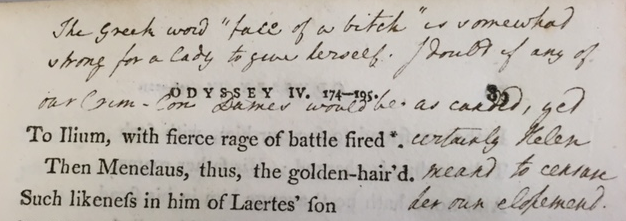

This writer seems to take great pleasure in pointing out the “absurdities” of Combe’s writing, but seems to be going by gut feeling, not empirical evidence. Though we might be tempted to characterize all of phrenology as a “pseudoscience,” it was respected in its era, making the real “pseudoscience” this pretentious yet decidedly faux-intellectual babble in the margins. Therefore, predicated solely on these traces, I would characterize this person as someone who has deluded himself or herself with prejudicial self-righteousness.We also have a nonverbal trace that corroborates not only this writer’s pompousness but also his or her racially biased view of society. On the page preceding the title page, we see a series of crude portraits drawn in profile:

This series of portraits, though rendered with little technical skill, presents enough detail that we can observe the pronounced differences between the white male and female portraits in the top row and the Black male portrait in the middle left (Indeed, his portrait is even subtitled with “nigers” [sic] and “caffres,” both antiquated — and now highly pejorative — terms for Black people in the plural that designate him as a generality, not an individual). We could interpret this as a descriptive exercise that objectively demonstrates the different features of people of different racial backgrounds, but since the portraits are in a book on phrenology, we should examine them phrenologically.

The first striking difference between the white male and the Black male portrait is the difference in the indentation between the head and the neck. This region corresponded to “Amativeness,” or “love between the sexes.” The white male’s skull dips profoundly into his neck to an unrealistic degree whereas the Black male’s skull flows almost directly into his neck. Therefore, we can judge that the “artist” here wished to convey that the white male possessed a small Amativeness faculty and the Black male a large faculty. Though “love between the sexes” does not seem to be a negative thing, a large Amativeness faculty was linked to deviant sexuality. This example of an assessment of a woman’s cranium elucidates this connection:

“Dr. Gall was led to the discovery of this organ in the following manner. He was physician to a widow of irreproachable character, who was seized with nervous affections, to which succeeded severe nymphomania. In the violence of a paroxysm, he supported her head, and was struck with the large size and heat of the neck” (Combe 109-10).

It is then possible that the person who drew the portrait wanted to confirm via phrenology the widely-held preconceived notions about Black sexuality. Marques P. Richeson draws from J.A. Rogers when observing that, even before the institution of slavery in the United States,

“This animalistic conceptualization naturally led to the stereotyping of black men as both hypersexual and hyperaggressive – “[i]n the Negro all the passions, emotions, and ambitions, are almost wholly subservient to the sexual instinct. . . .” (Richeson 103)

Furthermore, this perceived heightened libido was in turn tied to a diminished intelligence and an overall lack of personal control. This inverse proportion is also manifest in the pair of portraits: the forehead of the white male juts out in a once again exaggerated or unrealistic manner, whereas the forehead of the Black male barely makes provisions for the eye sockets. The area of the skull the artist probably intended to differentiate is the “Individuality” organ, and thus they perpetuate the idea that Black slavery could be justified by the entire race’s lack of agency.

The pair of portraits not only reveals a disdain for the Black race but also a personal bias. I am inclined to believe that, since the white male portrait is unlabelled yet appears first on the page that it may be a self-portrait. Even though this is impossible to know, it is at least most likely that the owner of this scientific book in 1838 North America was a white male. This would suggest that the aforementioned overwrought depictions of the white male’s neck dip and forehead crag seek to demonstrate the gentlemanly sexual restraint and the decisive individuality of the white male. The drawn portrait strikingly resembles the busts of famous men of politics and letters who are depicted in the Fowlers’ instructional book as well, further reinforcing my idea that this writer conceived of himself as being very distinguished and more intelligent than the author of his printed text.

We also see this supremacist view of the white male’s capacities in the fill-in chart at the front of the Fowlers’ book:

An interactive feature of the Self-Instructor, this chart lists all approximately 40 “conditions” and invites the autodidact to fill out the size of his or her capacities. According to the title page, we are reading “R.G. Tyler’s” phrenological assessment as conducted by “S. R. Wells” on June 29, 1865:

We note immediately that nearly every organ is listed as being either “large” with a value of 6 or “full” with a value of 5. The lowest value accorded is for the “Spirituality” organ, listed in the second column as a somewhere between a 4 and 3 for “moderate.” No organs are listed as 7 or “very large.” At first, we may be tempted to view this as a demonstration that the two men acknowledged Tyler’s faults as well as his strengths, but qualities such as a high Amativeness, “Destructiveness,” and “Combativeness” could be circumscribed by the constructs of virility and the Romantic notion of the fierce individual. When viewing this apparent willingness to present strongly — but not too strongly — in every possible category, it seems that these amateur phrenologists were not practicing objectively but instead armed with preconceived notions of white masculinity.

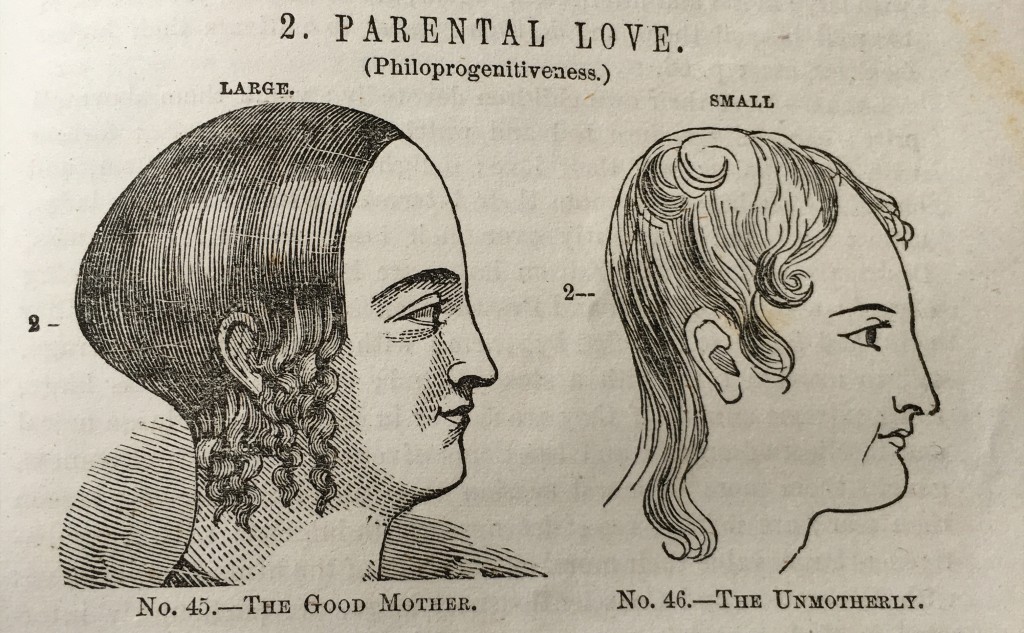

Lastly, in both of these phrenological volumes, very little attention is paid to female cranial traits. Though our artist did indeed draw a portrait of an elderly woman across from his white male, it is noteworthy that much of her skull is occluded by her bonnet. This eliminates the possibility of any conjectures as to such important traits as her sexuality (Amativeness, as previously discussed) and her conception of herself (“Self-Esteem” at the top of her skull). It even hinders our ability to draw conclusions about such “feminine” traits as her “Parental Love” (in the back middle of her skull), which represents one of the only qualities for which women are even depicted in the Fowlers’ volume:

Even in this science so obsessed with creating physical taxonomies for every trait of human life, an entire half of a species is flagrantly ignored and placed in neat, maternal boxes.

While phrenology may appear to be ridiculous, even humorous pseudoscience in retrospect, it is important to recognize how such a discipline affected the real lives of marginalized individuals. Divergence from the cognitive norm was typified, training people to recognize and even treat differently those bearing the telltale signs of “idiocy.” Phrenology was also used as a form of confirmation bias for race-based prejudice and characterized Black people and slaves as being morally inferior. Lastly, women were rarely discussed in this science that claimed to explain all of human behavior, diminishing the personhood of women and casting them as nothing more than mothers.

Phrenology, with its deeply rooted subjective biases, holds little weight in today’s data-driven science that prioritizes quantifiable evidence in an attempt to stave off confirmation bias. However, its legacy of prioritizing white, male physiology remains. Medical studies are just now making provisions for neural, racial, and gender difference in their experimental units. We can hope that, with an increased, authoritative understanding of how biological difference is not deviance, science will be further enriched to the point that we can laugh tomorrow at today’s biased methods just as we can laugh at phrenology.

Works Cited

Combe, George. A System of Phrenology. Boston: Marsh, Capen, and Lyon, 1838. Print.

Fowler, O.S. and L.N. Fowler. New Illustrated Self-Instructor in Phrenology and Physiology. New York: Fowler and Wells, 1859. Print.

Richeson, Marques P. “Sex, Drugs, and…: A Black Box Warning of Chemical Castration’s Potential Racial Side Effects.” Harvard BlackLetter Law Journal (25): 95-131. Web.

!["How absurd to suppose that the same faculty combines these pasions [sic] + different functions."](https://booktraces-library.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/PhrenologyHowAbsurd-1024x260.jpg)

![Four portraits presented in profile: top left of an adult male, top right of an elderly female, middle left of a Black male, captioned "Niger [sic], caffres" (both pejorative terms) middle right a bearded adult male rendered much smaller and possibly captioned "Jimmy." In the bottom center an amorphous front view of a possibly Black face.](https://booktraces-library.internal.lib.virginia.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/PhrenologyDoodles-650x1024.jpg)