Editor’s note: We are grateful to volunteer Jamie Rathjen for his continued work researching the histories of some of the uniquely modified books that were discovered in the course of the Book Traces @ UVA survey of the UVA Library’s circulating holdings. Here is Jamie’s latest guest post.

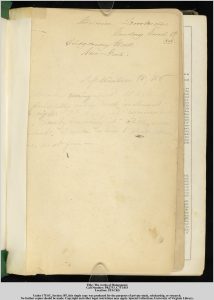

The “prominent citizen of Charlottesville” William James Rucker (1873-1941) donated much to the University, including some of his books which he appears to have inherited from his father-in-law, Micajah Woods (1844-1911). Woods was deeply connected with UVa, having graduated with a Bachelor of Laws degree in 1868 before becoming at the time the youngest ever member of the Board of Visitors, serving for four years from 1872. He was most prominently the long-serving commonwealth’s attorney for Albemarle County, holding the position from 1870 until his death. A particular book of Woods’, an 1825 London edition of The Works of Robert Burns, contains Rucker’s personal bookplate, depicting him at a lake with his hat in one hand and a freshly caught fish in the other. But the inscription comes from Woods instead – “Micajah Woods. 17 Febr. 1894. Please return if borrowed” – and it is both far from the only one in the opening pages and comes much later than the book itself and the other inscriptions.

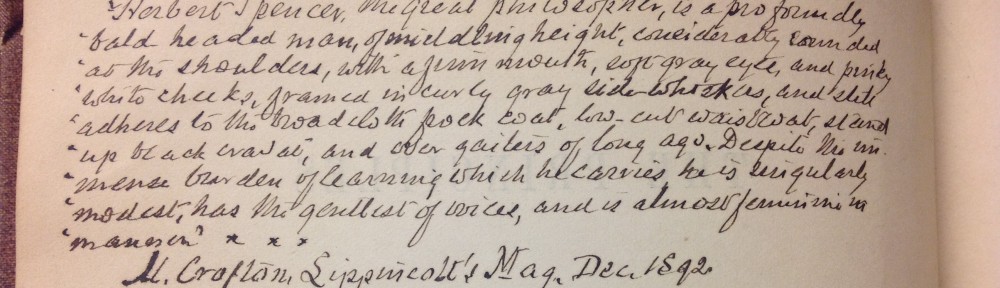

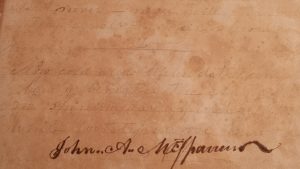

The Woods inscription stands out, large and dark, among a forest of simply names (two different ones) and the occasional date from about forty years before, in a variety of styles ranging from light, nearly-faded pencil to ink. One is repeated seven times in total: “John A. McSparran,” (born 1830) in whole or in part, as if for some sort of handwriting practice. Luckily, one comes with a date: “January 4th 1852,” indicating that these inscriptions much predate Woods and Rucker. Also present is a name repeated twice: “Erastus R. Brown,” and another McSparran, James (born 1833), shows up once. Erastus R. Brown (1834-1900) lived in Albemarle County in this period and later moved to Rucker’s home state of Missouri (although not near Rucker), and the McSparran family also lived in the county. The McSparrans’ father, Erasmus (born 1802), was a local carpenter and appears in a list of builders and workers to have constructed the Lawn and surrounding buildings, while James became an itinerant Methodist preacher around the state from 1853, listed in his church’s minutes as serving near Winchester and Washington early in his career. Because of this, he is the most well-documented of the three; a book of biographical sketches of the state’s Methodist preachers from 1880 reports that only James and his youngest sister were alive of the family.

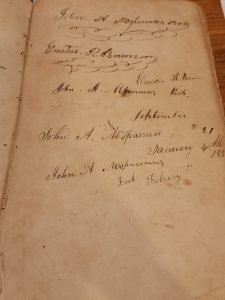

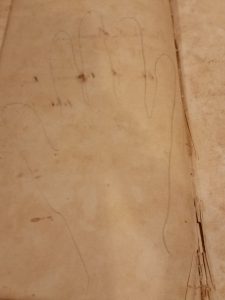

Returning to the books, the names, interestingly, appear as if they were done by the same hand and, for the two largest examples, the same pen. As for the writing itself, the entire body of it seems a bit juvenile: under Woods’ inscription there is some basic math in pencil, seemingly to work out the difference between 1833 and the 1850s, while on the next page after the names is a large outlined hand, again in pencil. Facing the title page is an engraving of Burns himself, which has been imitated both below the image and on the small piece of tissue paper which protects the image when the book is closed. Yet the most intriguing of all the inscriptions lies between the hand and the engraving: a faint poem simply titled “On Burns the Poet. June 4th 1851.”

The poem consists of a basic four stanzas of four lines, and appears to have an alternating rhyme (“ABAB”). However, the text is not entirely readable with my capabilities; the ends of the lines are in particular the most faded as to be nearly invisible. Additionally, it is unclear which of the three men wrote it, although a large “John A. McSparran” is in the middle of the page, in a thicker style than the rest of the text, and which overwrites the “3” indicating the third stanza. I have managed to decipher the first two stanzas to serve as a representative sample:

1.

The world may ever lust for thee

Thy heavy loss deplore

But never – never will there be

Thy equal on this shore

2.

Now cold and lifeless doth thou lie

Lonely beneath the clay and sod

No shining ray approach from the sky

While footsteps above thee are trod

The poem continues by lamenting Burns’ death yet taking solace in his perceived irreplaceability. The date of 1851 and the handwriting, similar to the preceding pages, limits it to one of the three inscribers. Curiously, for how heavily the book is marked before the text starts, there is no marking of the text itself. The text’s layout, because of Burns’ voluminous work and the additional essays included, consists of double columns and small print and is not conducive to even underlining or other non-verbal marginalia. Yet whichever of Brown or the McSparrans wrote the poem seems to have been a devoted fan of the poet.

Despite possessing no connection to UVa except through his father-in-law Micajah Woods, the Missouri native Rucker came to greatly benefit the university through his donations. A number of his and Woods’ letters, papers, notebooks, and other writings are kept in Special Collections. Among the most interesting is a collection of letters, some to Woods (but none to Rucker) from prominent 19th century and mostly Virginian figures, including Andrew Jackson, John Marshall, John C. Calhoun, and Charles Dickens. These are prized for their famous writers and subjects; those who wrote to Woods himself or his grandfather, also named Micajah, include Jeffersonian politician John Randolph, Confederate governor of Virginia John Letcher, Congressman and rector of the University Alexander H. H. Stuart, and Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston. Woods served in the Confederate cavalry and horse artillery from 1862, when he turned 18 and was allowed to leave the University, to the end of the war. Additionally, letters to his parents including “detailed descriptions” of battles in which he participated, such as Second Manassas and Antietam, survive in the collection of his papers. As for Rucker, his most significant donation came in 1941 in the form of $50,000 to go towards building a home, called the Rucker Home for Convalescent Children, under the auspices of the University hospital. The money was used to buy an estate west of Grounds on Ivy Road, but the home, as named for Rucker, only lasted 15 years until it was rebuilt in 1956-57.

Rucker’s contributions to UVa, including this book, thus are derived significantly – although not entirely – from Woods, who appears to have been much more well-connected than him: the record of a court case over his will states that Rucker, “though a man of cultured tastes and wide information, had few intimate friends.” In the same way as Rucker’s contributions at large, the interesting aspects of this book are again derived entirely from others (and Woods). Nonetheless, this book and any others that Rucker donated, whether or not they came from Woods, represent a valuable contribution to UVa from two prominent residents of the area.

Works Cited

Currie, James, M.D. The Works of Robert Burns. London: Jones and Co., 1825.

Lafferty, John J. “Rev. James Erasmus McSparran.” Sketches of the Virginia Conference, Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Richmond: Christian Advocate Office, 1880. 112. https://books.google.com/books?id=72bUAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA112 &hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwjJ95atzeHVAhXpgFQKHWcnCzM4ChDoAQgvMAI#v=onepage&q&f=false

Wilson, Richard Guy. “The Builders and Workers of Thomas Jefferson’s Academical Village.” Building a Living Legacy: Jefferson’s Academical Village. The Fralin Museum of Art. 27 February 2009. http://www.uvamblogs.com/jeffersons_academical_village/?p=235

“Sheridan v. Perkins.” FindACase, va.findacase.com/research/wfrmDocViewer.aspx/xq/fac.19470609_0040061.VA.htm/qx.

“History of the University of Virginia Hospital in the 1950s and 1960s.” The University of Virginia Hospital Celebrating 100 Years. http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/centennial/growth_part2/

“A Guide to the Micajah Woods Papers.” Special Collections Department, University of Virginia Library. http://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=uva-sc/viu00001.xml

Minutes of the Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. Nashville: Southern Methodist Publishing House, 1859. 137, 141, 242. https://books.google.com/books?id=N3ozAQAAMAAJ&lpg=PA137&ots=5Rqmy2o85&pg=PA1#v=onepage&f=false

Names, dates, locations, and occupations from ancestry.com