Post by UVA English Department research assistant Maggie Whalen.

Book Traces @ UVA recently happened upon this 1872 edition of Mary T. Tardy’s The Living Female Writers of the South in the UVA Library Collection.

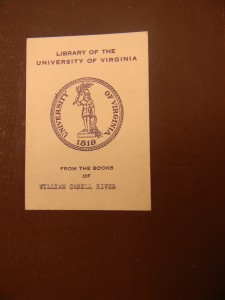

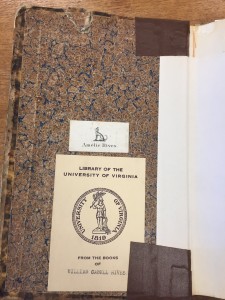

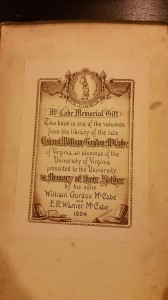

A bookplate reveals that the text came to UVA through the books of William Cabell Rives (1793-1868).

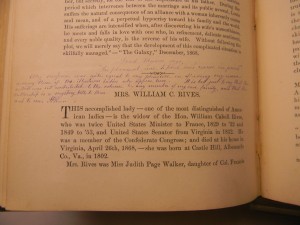

As the title suggests, the book contains the biographies of southern female authors alive in the 19th century. Its pages are entirely unmarked, save for a few noteworthy annotations on the three-page biography entitled “Mrs. William C. Rives.”

Above the section’s title, a hand has left the following note:

Lord Byron says, ‘Tis pleasant, sure, to find one’s name in print.’ My surprise was quite equal to my pleasure in finding my name among those of the illustrious ladies who appear here. It is but just to say that this notice was not contributed to the volume by any member of my own family, and that the authorship is a mystery both to them and to me. JPR…. (436)

Judith Page Rives (1802-1882), wife of William C. Rives, describes the surprise and honor she feels at finding her biography in Tardy’s text. The content and tone of the note suggest that it is not entirely self-reflective, but also directed at any reader who might happen upon the book in the future.

In the biography that follows, Rives has made a few corrections to the text. She adjusts the date of France’s July Revolution from 1820 to 1830. She corrects the spelling of her daughter’s name, Amélie (chosen for her by her godmother, the Queen of France), directly in the text and then transcribes it in the margins for clarity. Finally, she changes the title incorrectly attributed to her second book from “Home and Abroad” to “Home and the World.”

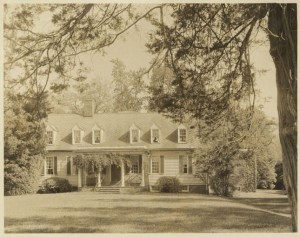

Aside from these minor adjustments, Rives does not interfere with the anonymous biographer’s account of her life, suggesting, perhaps, its accuracy. The notice describes Rives as “a faithful mother” of six and a “most useful helpmeet to her husband,” who served twice as United States Minister to France and once as a Senator from Virginia (438). She is further characterized as “a prominent and yet ever beneficent leader in society,” most notably in her native Albemarle County (438). There, she and her family resided in a vast, historic estate called Castle Hill (on the market now for $11.5 million) and mingled with the likes of Madison and Jefferson. Finally, Rives’s biographer describes her as “an author of more than ordinary ability and popularity” (438).

“Castle Hill,” from Charles F. Gillette Photographs, 1905-1970, Accession #11083, Special Collections Dept., University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Among Judith Rives’s literary achievements are two books: Souvenirs of a Residence in Europe (1842) and Home and the World (1857). The biography quotes from a review contemporary to the publication of Souvenirs, saying: “This book is distinguished throughout for its moral and elevated tone. Its style, which perhaps in some instances may be rather luxuriant, is generally chaste, fluent, and graceful” (437). According to Jane Censer, author of The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood, much of Rives’s work was nonfiction, based on her travels abroad and her life at Castle Hill. Censer also notes that many of the women included in Tardy’s Female Writers of the South came from “well-to-do” Southern families and published a single article, poem, or novel, often with a local printer (214). A number of these women “published so little or in such obscure journals that the modern researcher can find almost none of their printed efforts” (214). Judith Rives is certainly a slight break from the “authors” Censer describes, having published Souvenirs with a Philadelphia publishing house and Home and the World with a publisher based in London. A single copy of Rives’s Tales and Souvenirs of a Residence in Europe (below) is available in the UVA Library circulating collection. Several copies of Souvenirs and Home and the World are held in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

Judith Rives was not the only writer in her family. In the later years of his life, her husband, William Cabell Rives, wrote biographies of John Hampden and James Madison, both of which are available in the UVA Library circulating collection. Their daughter, Amélie Louise Rives Sigourney (1832-1873) also dabbled in writing, penning but never publishing a number of poems and stories before her death.

The most notable writer among the Riveses, though, was surely Judith’s granddaughter and Amélie Rives Sigourney’s niece, Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy (1863-1945). Goddaughter of Robert E. Lee and eventual heiress of the Castle Hill estate, Amélie ran in the same circles of Albemarle society as her grandmother had. Unlike her grandmother, though, Amélie’s celebrity was not only local, but national. Amélie’s fame was due in large part to her first novel, The Quick or the Dead? (1888), which was an immediate sensation. The book, which dared to depict women as sexually aware, was “reviled by critics and clergymen across the country,” but nonetheless sold 300,000 copies (Lucey). Amélie proceeded to publish at least 24 volumes of fiction, a number of uncollected poems, and a play. According to Censer, Amélie was part of a small group of southern female authors who in their works “presented southern women who were intellectually astute and domestically skilled. Their heroines neither sought nor enjoyed belledom but instead searched for fulfilling, useful lives” (8). Amélie, in particular, experimented with gender conventions and on occasion confronted the more difficult topics of race and class (Censer 8).

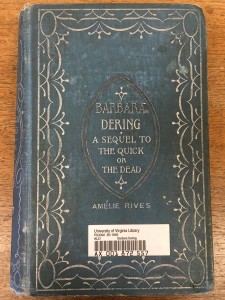

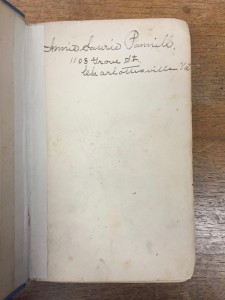

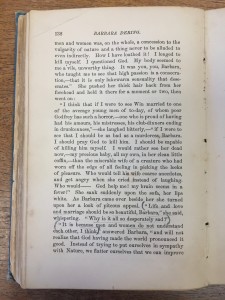

The UVA Library Collection contains a number of books associated with Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy, including those written by her and others owned by her. This copy of Barbara Dering, Amélie’s 1893 sequel to The Quick or the Dead?, is thoroughly marked, featuring the inscriptions of at least two distinct owners and marginalia throughout.

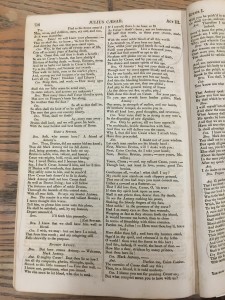

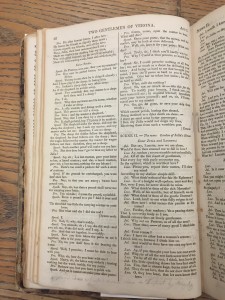

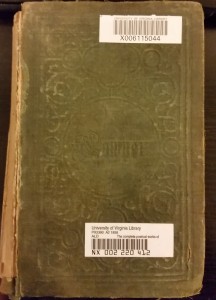

The circulating collection also contains a thick copy of Shakespeare’s plays, formerly owned and heavily annotated by Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy herself.

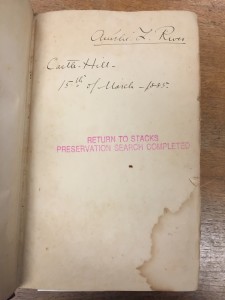

Amélie inscribed the volume with her name multiple times. The first example appears on the front endpaper and reads: “Amélie L. Rives / Castle – Hill / 15th of March – 1885.” At the time of this initial inscription, Amélie was just 22-years-old, still three years from publishing The Quick or the Dead?.

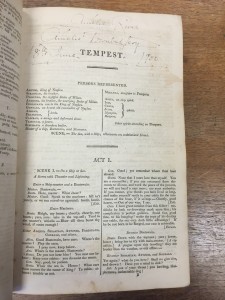

A second inscription appears on the title page of The Tempest. Here, Amélie has inscribed her name twice, first with her maiden name, “Rives,” and a second time with her married name, “Troubetzkoy.” The names are accompanied by a date: “18th June 1900.” At the time of this inscription, Amélie was 37-years-old and had published a number of novels. Though she had married the noble but impoverished Pierre Troubetzkoy four years prior to this inscription, Amélie continued to publish her literary works under her maiden name, perhaps explaining the double signature.

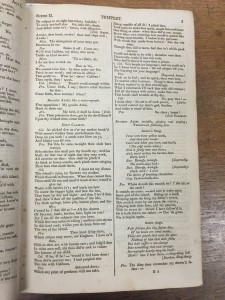

Many passages of the plays that follow are bracketed, check-marked, and underscored.

Amélie has also left several notes throughout the volume. In The Gentleman of Verona, for instance, Amélie stars and brackets several lines of text at the end of Scene I and writes at the bottom of the page: “Same idea exposed several times in Tempest by Gonzalez.”

Later, in Much Ado About Nothing, she notes: “In Shakespeare’s time ‘ache’ was pronounced ‘H’ – AR.”

In the margins of Taming of the Shrew, she seems to make a wry joke about husbands, marking the line: “A husband! a devil!” and writing at the bottom of the page: “The book opened here of itself just as I had said laughingly ‘O gin I had a husband!'” According to the Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “gin,” this exclamation might translate roughly to “If only I had a husband.”

Perhaps the most intriguing of Amélie’s annotations appears in All’s Well That Ends Well. Here, Amélie marks an “X” beside the line: “So there’s my riddle, One, that’s dead, is quick,” and writes below: “The book also opened here just as I was trying to find another title as good as The Quick or the Dead. 23 Nov. 1888.” In this moment, we witness an intimate memorialization: Amélie marks in her copy of Shakespeare’s plays the phrase that inspired the title of her most famous literary work, published just half a year prior in April 1888.

From Judith Rives’s humble response upon finding her name in Female Writers of the South to her granddaughter Amélie Rives’s remarks and reminiscences upon Shakespeare, it is clear that the UVA Library Collection contains an array of Rives family literary treasures, not only those printed by press but also those marked by hand.

Sources

“The Cabell Family.” Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. University of Virginia Library, n.d. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Censer, Jane Turner. The Reconstruction of White Southern Womanhood, 1865-1895. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2003. Google Books. Google. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Hatch, Peter J. “The Garden and Its People.” “A Rich Spot of Earth”: Thomas Jefferson’s Revolutionary Garden at Monticello. N.p.: Yale UP, 2012. 33. Google Books. Google. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Lay, K. Edward. “The Georgian Period.” The Architecture of Jefferson Country: Charlottesville and Albemarle County, Virginia. Charlottesville: U of Virginia, 2000. 60-61. Google Books. Google. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Lucey, Donna M. “Patron’s Choice: Sex, Celebrity and Scandal in the Amélie Rives Chanler Troubetzkoy Papers.” Notes from Under Grounds. University of Virginia Library: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections, 23 Aug. 2013. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Prose, Francine. “Lifestyles of the Rich and Infamous”. The Washington Post. Web. 30 Jul, 2006.

Rives, Amélie. Barbara Dering. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott company, 1893.

Shakespeare, William, et al. The Plays of William Shakespeare. New ed. London: Printed for F. C. and J. Rivington; [etc., etc.], 1823.

Tardy, Mary T. The Living Female Writers of the South. Philadelphia: Claxton, Remsen & Haffelfinger, 1872.

Varon, Elizabeth R. “We Mean to Be Counted”: White Women and Politics in Antebellum Virginia. N.p.: U of North Carolina, 2000. Google Books. Google. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.

Weeks, Lyman Horace. “George Lockhart Rives.” Prominent Families of New York. New York: Historical, 1897. 478. Google Books. Google. Web. 27 Jan. 2016.