| Post by UVA English Department research assistant Maggie Whalen.

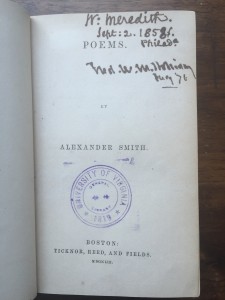

Book Traces @ UVA recently found this 1853 copy of Alexander Smith’s Poems in the UVA Library Collection.

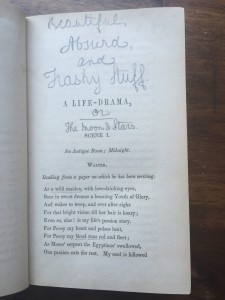

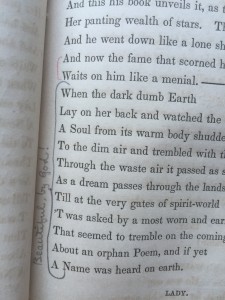

Flipping through the book’s pages, one immediately notices the abundance of notes scrawled in its margins. Indeed, more pages than not include some evidence of a previous reader’s interaction with the text.

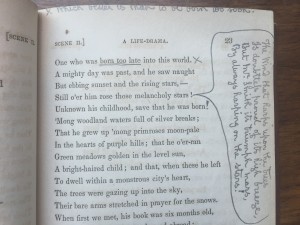

Smith’s Poems contains four titled lyrics: “A Life-Drama,” “An Evening at Home,” “Lady Barbara,” and “To —,” as well as several untitled sonnets. First, longest, and most heavily annotated is the 150-page play “A Life-Drama.”

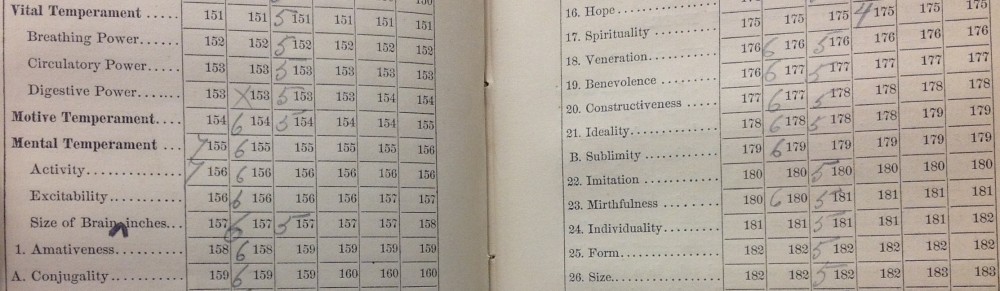

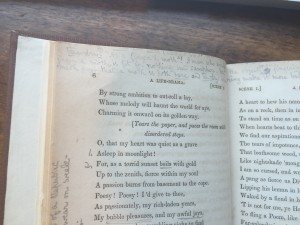

An initial example of marginalia pops up on the first page of this first poem. Above its title, the reader has written in pencil: “Beautiful, Absurd, and Trashy Stuff.” Below, the same hand has extended the play’s title: “A Life-Drama, or The Moon & Stars” (5).

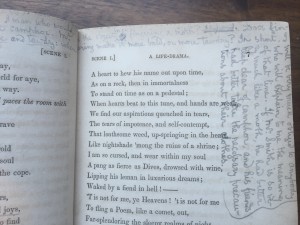

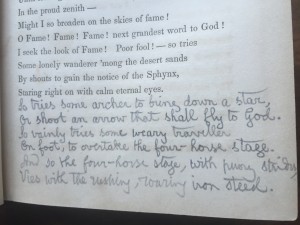

In the pages that follow, the same reader develops in the margins his own system of notes. He scrutinizes and satirizes Smith’s poetry, making verbal and nonverbal annotations of the text, additions and amendments to the text, and citations of literary allusions made within the text.

All of this causes a present-day reader to wonder: Who wrote these ridiculing comments? And, what was his beef with Alexander Smith?

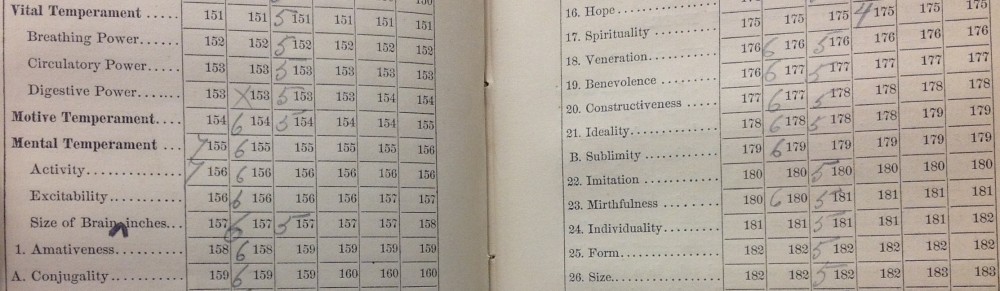

Conveniently, the book’s title page features the inscriptions of two former owners. First is “W. Meredith,” who seems to have inscribed his name on September 2, 1853 in Philadelphia. The precise year of signing is unclear, as the final digit has been blotted out and corrected. Beneath is “Fred. W. M. Holliday,” accompanied by the date “July ’76.”

A handwriting expert I am not, but the highly legible, looping quality of the penmanship in the book’s marginalia resembles much more closely the signature of W. Meredith than that of Fred. W. M. Holliday.

Unfortunately, the first inscription does not provide sufficient information to definitively identify W. Meredith. A number of men bearing some variation of the name “William Meredith” were alive during the 1850s. As far as I could tell, none could be linked directly to the book’s other owner, Governor Frederick William Mackey Holliday. However, there is considerable evidence suggesting that the book belonged at one point to either William Morris Meredith (1799-1873) or his son William Keppele Meredith (1838-1903), both of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

William Morris Meredith, the elder, was a prominent Philadelphia lawyer. He also served as United States Secretary of the Treasury between 1824 and 1828. The Meredith Family Papers are preserved at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Among them are some of his personal writings, including an assortment of original poetry and three of his diaries. The second of these diaries opens with an entry written on the eve of his twentieth birthday, at which point he had been practicing law for some time. He reflects:

Eighteen months have elapsed since I commenced the practice of my Profession. My profits have been small and the sincere disgust which I have always entertained for the Law has rather increased than diminished during that period. But after mature consideration, I can discover no other pursuit in which I could engage with any prospect of success. My inclinations urge me to a literary life, but that yields no expectations of an immediate support, and I feel it my duty to relieve my father as quickly as possible from so heavy and useless an encumbrance as myself.

William Morris’s love of literature is made evident also by the presence of his original verse, most of which was probably written before his legal career began. Notes on the Meredith Family Papers indicate that most of William Morris’s poems consist of “light and witty commentary on women and courting.”

William Keppele Meredith, son of the former, attended Princeton between 1851 and 1853. Plagued from childhood with cataracts and a speech impediment, William Keppele took a leave of absence from Princeton in 1852 and left school permanently in 1853. He returned to Philadelphia and spent most of his life as a “man of leisure,” save for a brief stint as a Union General’s secretary during the war. Meredith went on to become a published writer of both essays and poems. The Meredith Family Papers contains several of William’s original poems, in which he discusses “patriotism, love, adultery, religion, and philosophy.”

It seems entirely possible that either of the Merediths might have at one point owned, and annotated, this volume of Alexander Smith’s Poems. The two shared a love of literature and an affinity for writing verse. If the book was indeed signed in September 1853, 54-year-old William Morris would have been practicing law in Philadelphia and 17-year-old William Keppele would have just returned to Philadelphia from Princeton. Without access to the family’s records kept in Philadelphia or the ability to conduct a handwriting analysis, conclusions are quite difficult to draw.

Information on the book’s second owner is decidedly more distinct. Governor Frederick W. M. Holliday (1828-1899), a Virginia native, graduated Yale University in 1847. Less than a year later, he acquired degrees in philosophy, political economy, and law from the University of Virginia in 1848. Holliday proceeded to open his own law practice in Frederick County, where he was elected the Commonwealth’s Attorney for three consecutive terms beginning in 1851. An avid secessionist, he served as a captain in the Confederate Army, and was later promoted to major and lieutenant colonel. He was forced to resign his commission after he was wounded in battle and his arm was amputated. Following the war, Holliday returned to law and was elected governor of Virginia in 1878. At the end of his governorship, he retired and devoted the remainder of his life to traveling. It was Governor Holliday who ultimately donated this edition of Poems to the UVA Library Collection.

The question of connection between the Merediths and Governor Holliday might be answered by their common involvement in the practice of law or participation in the Civil War. It is also possible that the men were unknown to each other and happened upon the book independently.

Regardless of the note-taker’s identity, this volume stands out for its profusion of readerly commentary, much of which is pointed, funny, and smart. History reveals that this reader was not alone in ridiculing Alexander Smith’s Poems.

When Poems debuted in 1853, Smith was initially praised as the next great British lyricist. Following the book’s publication, Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, an American literary journal, proclaimed that “A Life-Drama” had just “received a more universal and flattering welcome than was ever before awarded to an English poet” (LaPorte 421). Shortly thereafter, though, praise turned to criticism, which consisted of vicious attacks and accusations of plagiarism. Most damning was literary critic W.E. Aytoun’s 1854 review of Poems, in which labeled Smith a Spasmodic. The Spasmodics, a group of mid-19th century poets, closely imitated the Romantics and were criticized for their excessive use of natural imagery and obscure allusions. Smith resisted the title and spent the remainder of his life trying to shake his association with the group. Later in 1854, an anonymous author published a parody of Smith’s “A Life-Drama” entitled The Firmilian: A Tragedy, causing further damage to his reputation. Smith ultimately turned to writing essays, for which he received less attention but better critical reception.

Looking more closely at the notes made in this copy of Poems, and more specifically those made on “A Life-Drama,” it becomes clear that this volume is engaged in a larger historical conversation about Alexander Smith.

In “A Life-Drama,” a poet named Walter falls deeply in love with an unnamed lady. After meeting in an Italian forest, the two engage in extensive flirtation. To Walter’s dismay, though, his beloved is doomed to marry an old, wealthy man. Time passes and Walter overcomes his heartbreak, ultimately falling in love with another woman, Violet.

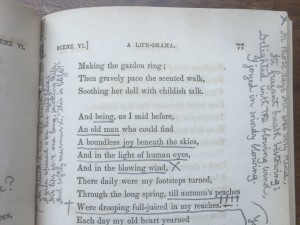

Some of the reader’s comments on the play come as brief quips: “Nonsense” (23), “Absurdity” (24), “What stuff and nonsense!” (35), “You sentimental old hypocrite!” (77), “Every idea in this Poem is repeated five times at least” (82), “Ain’t they a pair of wiseacres!” (86), “Unnatural” (131), and “Disgusting Affectation” (131).

The few positive comments that do appear resonate as sarcastic given the generally disgruntled tenor of the reader’s commentary. Beside several lines of bracketed verse in Scene II, for example, he writes: “Beautiful, by God!” (19) Another bracketed passage in the same scene is accompanied by the note: “Love is sometimes said to be incomprehensible” (13).

Other notes are more long-winded. In Scene I, for example, Walter declares: “Bare, bald and tawdry, as a fingered moth / Is my poor life; but with one smile thou canst / Clothe me with kingdoms” (6). In the margins above, the reader reacts:

‘As a finger’d moth!’ A man who would finger a moth, is fit for nothing but camphor [moth repellant]. Mr. Smith says that a moth is both ‘bare and tawdry:’…. Does fingering a moth make it more bald, or more tawdry? In short, I will be very much obliged to anybody who will explain to me the meaning of that line. If Mr. Smith is so very much like a moth, he had better keep clear of camphor, and his friends had better take the necessary precautions about their clothes. (6-7)

Unfortunately, the edges of many pages were trimmed during the volume’s re-binding, so some notes, including the one transcribed above, are abbreviated.

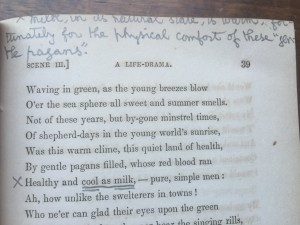

In Scene III, Walter speaks of “gentle pagans…whose red blood ran / Healthy and cool as milk,” to which the reader responds: “Milk, in its natural state, is warm fortunately for the physical comfort of these ‘gentle pagans’” (39).

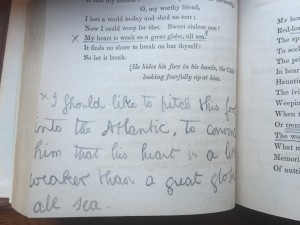

In Scene V, Walter declares: “My heart is weak as a great globe, all sea,” provoking the reader to write in large, angry letters: “I should like to pitch this fool into the Atlantic to convince him that his heart is a little weaker than the great globe, all sea” (74).

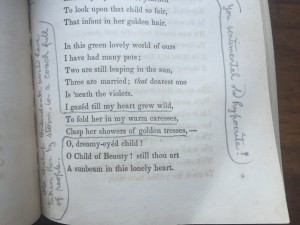

In Scene VI, Walter recites following lines: “I gaz’d till my heart grew wild, / To fold her in my warm caresses, / Clasp her showers of golden tresses” (77). In the margins, the reader reacts to this sensuous description: “Old Bishop Onderdonk would have taken her by storm, in a coach full of people” (77). The reader here makes reference to the contemporary controversy surrounding Bishop Benjamin Treadwell Onderdonk (1791-1861). In 1844, multiple female parishioners, including the wife of one of his fellow clergymen, accused the Episcopal Bishop of New York of sexual misconduct. The scandal remained in contention for over a decade.

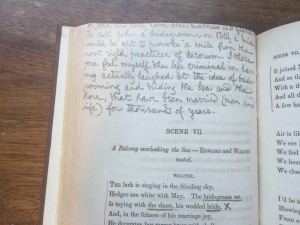

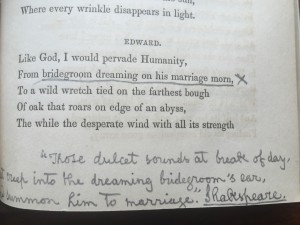

In Scene VII, Walter gazes out over the sea and remarks: “The bridegroom sea / Is toying with the shore, his wedded bride, / And in the fulness of his marriage joy, / He decorates her tawny brow with shells” (90). The reader underscores “bridegroom sea,” “the shore,” and “bride,” and then responds in a marginal note:

John and Polly have been married 40 years. To call John a bridegroom, or Polly a bride, would be apt to provoke a smile from the most rigid practicer of decorum. I therefore feel myself the less criminal in having actually laughed at the idea of bridegrooming and briding the Sea and the Shore, that have been married (man and wife) for thousands of years. (90)

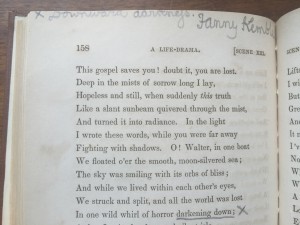

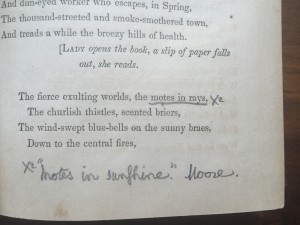

In other moments, the reader identifies Smith’s literary allusions, calling to mind contempoary accusations that he had plagiarized portions of Poems. William Shakespeare, Thomas Moore, and Fanny Kemble are each cited several times.

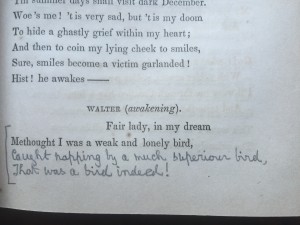

The majority of the reader’s notes, however, take the form of original verse, extending and satirizing Smith’s poetry. For example, upon waking from a nap in Scene II, Walter says: “Fair lady, in my dream / Methought I was a weak and lonely bird,” at which point the reader interjects: “Caught napping by a much superior bird, / That was a bird indeed!” (15)

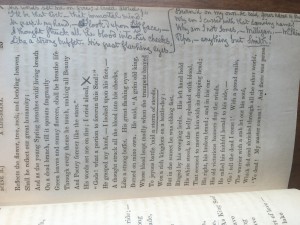

Later in the same scene, as Walter speaks to his unnamed love interest he says: “His words set me on fire; I cried aloud” (25). The reader repeats this line in his note and then continues:

‘I’ll be that Poet—that immortal mind!’

He grasp’d my hand,—I look’d upon his face,—

A thought struck all the blood into his cheeks,

Like a strong buffet. His great flashing eyes

Burn’d on my own. He said, ‘Your name is Smith.’

Why am I cursed with that damning name?

Why am I not Jones, —Milligan, —McShinn,

Pips, —anything but Smith! (25)

Throughout the entire play, the reader continues to interject, adopting the Smith’s style even as he mocks the poet and his characters. In these moments, the reader’s actions echo, or perhaps foreshadow, the anonymous author’s 1854 parody of “A Life-Drama,” The Firmilian: A Tragedy. Included below are a few further examples, which I have abstained from transcribing for the sake of space.

A final instance worth mentioning explicitly appears on the poem’s final page. Smith’s Walter delivers the final words of the play to Violet, his second lover. The reader extends Walter’s speech, and also allows Violet a response:

Yes, Walter! I will sleep upon thy breast,

As yonder moon sleeps on the quiet river.

The stars, and he in the moon, are looking at us,

So come away, for I’m afraid of blushing. (160)

In a final jab, the reader grants Walter the last line. Ever the romantic, he replies to his love: “You look more pale than ever” (160).

Comments like these appear also in the margins of the volume’s subsequent, shorter poems.

So rich in user intervention, so shrouded in mystery, and so embedded in the literary critical context of its time is this copy of Alexander Smith’s Poems that extensive additional research could be conducted on its history.

Sources

“Benjamin Treadwell Onderdonk.” House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College. Dickinson College, n.d. Web. 10 Dec. 2015.

“camphor, n.” OED Online. Oxford University Press, December 2015. Web. 9 December 2015.

Executive letter books of Governor Frederick M. W. Holliday, 1878-1881. Accession 33431, State government records collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

“Introduction” Nineteenth-Century Literary Criticism Ed. Denise Evans and Mary L. Onorato. Vol. 59. Gale Cengage, 1997. 5 Dec, 2015.

LaPorte, Charles, and Jason R. Rudy. “Editorial Introduction: Spasmodic Poetry and Poetics”. Victorian Poetry 42.4 (2004): 421–428. Web.

“Poems by Alexander Smith.” Bizarre: For Fireside and Wayside. Vol. 3. N.p.: Church, 1853. 121-23. Google Books. Web. 9 Dec. 2015.

Series 7, William Morris Meredith: William Meredith, Meredith Family Papers (Collection 1509), The Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Smith, Alexander. Poems. Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1853. Print.

|

|

|