Post by UVA English Department research assistant Maggie Whalen.

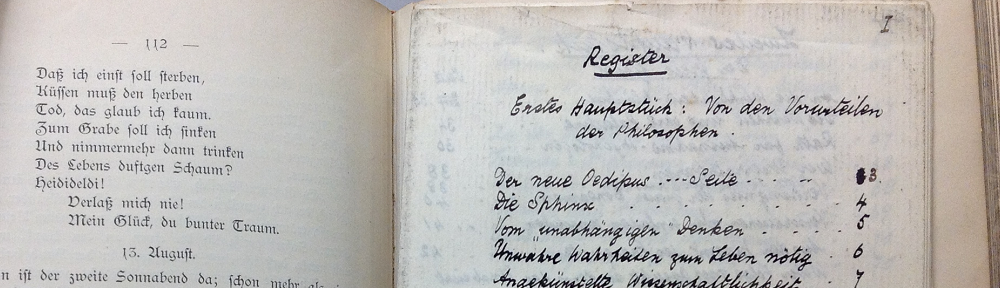

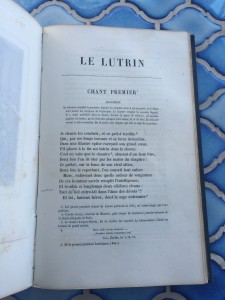

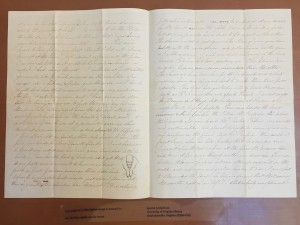

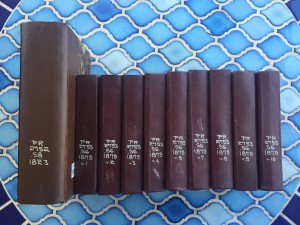

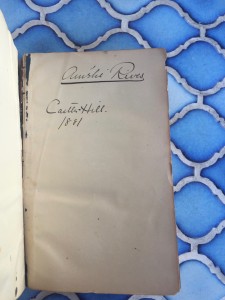

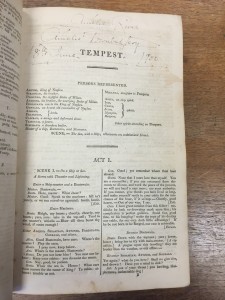

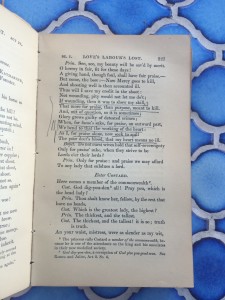

The Book Traces @ UVA team recently happened upon this 1885 edition of Rose E. Cleveland’s George Eliot’s Poetry, and Other Studies in the UVA Library’s circulating collection.

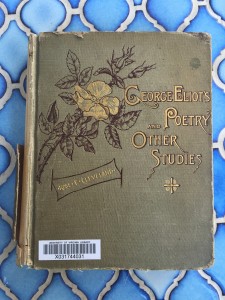

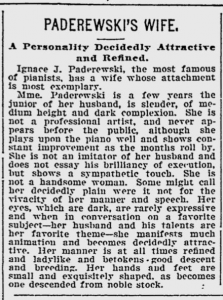

Wedged between pages 88 and 89 is a photograph of a young woman in profile, clipped from a newspaper. A caption below identifies her as Madame Paderewski.

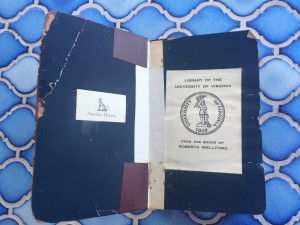

The volume is otherwise unmodified, save for a library-administered bookplate inside the front cover, which indicates that it came to UVA through the books of one Paul B. Victorius.

This volume and its modifications provoke a number of questions, some answered more easily than others. Who, for example, is this Madame Paderewski? Who so carefully removed her image from a newspaper? And why did this admirer of Paderewski choose to preserve her likeness in a book of criticism on George Eliot?

The clues provided by this text are so limited that forming concrete connections between the various implicated parties (owner, author, photographic subject) proved to be a challenge. Inconclusive it may have been, but the investigation yielded tales that were nonetheless colorful and complex.

The search began naturally with a look into the biographies of each character in this unlikely crew.

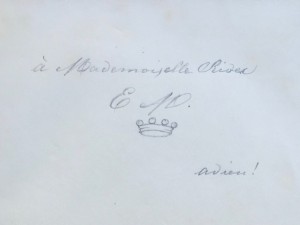

Rose Elizabeth Cleveland (1846-1918), author of the text in question, was a writer, editor, lecturer, and the First Lady of the United States during the first of her brother Grover Cleveland’s two terms as President. She published George Eliot’s Poetry, and Other Studies, her first book, while in the White House in 1885. She was notably the first First Lady to publish a book during her incumbency. The following year, she published a 545-page treatise called You and I: Moral, Intellectual, and Social Culture. She continued to write and publish until 1910. Despite her work as a writer and an educator, Cleveland is best remembered for her affair with Evangeline Simpson and for the passionate series of love letters that the two women exchanged. Theirs was a tumultuous relationship, but ended peacefully in Italy, where the two were eventually buried together.

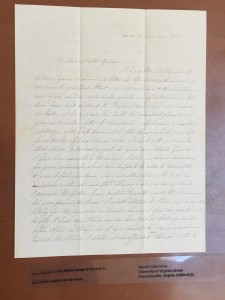

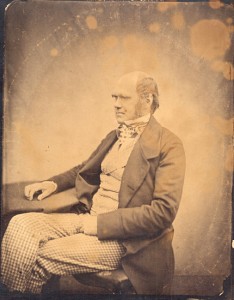

Photo: Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

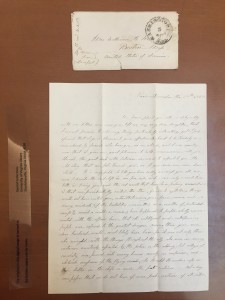

Paul Bandler Victorius (1899-1970), donor of the text in question, was an American collector of rare books and manuscripts with a particular interest in materials related to evolution and Darwin. Born in New York, Victorius moved as a young man to London with the intent of studying medicine. Shortly after arriving, however, he dropped out of school and opened a bookshop. Victorius returned to the United States in 1940 following the destruction of his store in World War II. He eventually settled in Charlottesville and opened a framing business called Freeman-Victorius on UVA’s Corner, where it remained until 2014.

Photo: Sloan Manis Real Estate Partners.

Victorius had, by that time, amassed a collection of Darwin-related materials that was “reputedly the largest and finest in the world,” with the singular exception of the one owned by Darwin himself (“Paul Victorius Evolution Collection”). In 1949, Victorius made a partial gift of his entire collection of Darwin-related material to the UVA Library. The remainder of the collection was subsequently purchased with funds from an anonymous donor. UVA thus found itself in possession of over 800 books and 150 manuscripts relating to the discoveries of Charles Darwin and his contemporaries. The Paul Victorius Evolution Collection is housed in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. Victorius continued to run his Corner frame shop with business partner Richard Freeman until his death in 1970.

Photo: Encyclopædia Britannica.

Finally, Helena Gorská Paderewski (1856-1934), the subject of the photograph loosely inserted in the text, was a Polish social activist and the wife of renowned musician, composer, and Polish statesman, Ignacy Jan Paderewski (1860-1941). Ignacy, a classically trained pianist, enjoyed international fame for his musical talents and eventually developed into a Polish diplomat. During World War I, Ignacy served as Prime Minister and Foreign Minister of Poland. Helena Gorská, meanwhile, organized Polish refugees in Paris in producing and selling dolls dressed in traditional Polish garb, the profits of which were used to the aid of Polish war victims. Helena, who spent the last part of her life seriously ill, is remembered today primarily for this philanthropic project. The dolls, still referred to as “Madame Paderewski’s dolls,” are now rare collectibles sell for many hundreds, and sometimes even thousands, of dollars.

A contemporary photograph of Paderewski’s dolls. Photo: Library of Congress.

Modern photographs of Paderewski’s dolls. Photos: “Three Cloth Dolls,” Theriault’s and “Very Rare French/Polish Doll,” Theriault’s.

In this book, the complex lives of three seemingly unrelated characters intersect.

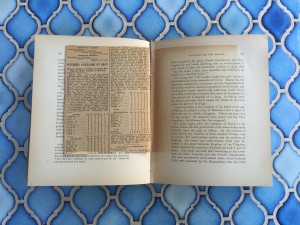

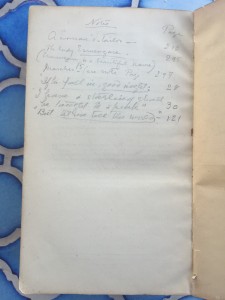

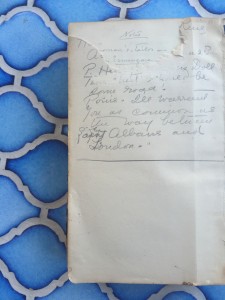

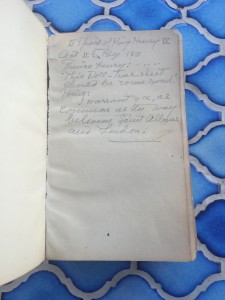

Without much else to go on, the search continued with an effort to determine the clipping’s origin, an endeavor made possible by text on its backside.

Fragments of several articles report the outcomes of July 8th baseball games between Boston and the Athletics, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, Cincinnati and Brooklyn. A search through the Boston Americans’ historical rosters for players named Dougherty, Collins, Stahl, Gleason, and Parent narrows the year of publication to 1902. Mention of the Philadelphia Athletics, the Philadelphia Phillies, and the Pittsburgh Pirates hints that the clipping originated in a Pennsylvania newspaper. That one article begins “Special to ‘The Record’,” prompts a search for Pennsylvania periodicals called “The Record.” This search yields evidence of The Philadelphia Record, a daily newspaper active between 1877 and 1947.

Sure enough, nestled within a section called “Womankind” in the July 9, 1902 edition of The Philadelphia Record is the photograph of Madame Paderewski. Accompanying the image is an anonymously authored article: “Paderewski’s Wife: A Personality Decidedly Attractive and Refined.”

The brief article does not provide the full name of its subject, identifying her instead with respect to her husband, Ignace J. Paderewski, “the most famous of pianists.” The author observes that Madame Paderewski is “slender, of medium height and dark complexion” and possesses hands and feet that are “small and exquisitely shaped, as becomes one descended from noble stock.” Despite these merits, the author says: “She is not a handsome woman. Some might call her decidedly plain were it not for the vivacity of her manner and speech. Her eyes, which are dark, are rarely expressive.” Regarding her musical abilities, we learn that she “is not a professional artist, and never appears before the public, although she plays upon the piano well and shows constant improvement as the months roll by.” The author further notes: “She is not an imitator of her husband and does not essay his brilliancy of execution, but shows a sympathetic touch.” We learn that Madame Paderewski’s “favorite subject” of conversation is “her husband and his talents.” Indeed, when discussing Ignace, “she manifests much animation and becomes decidedly more attractive.” Despite her several shortcomings, the author concludes that Paderewski’s wife’s “manner is at all times refined and ladylike and betokens her good descent and breeding.”

This article, published just three years after Helena and Ignacy wed in 1899, reads almost as if a review of Helena’s (apparently limited) merits. Given the snarky tone of the piece, it seems almost surprising that a reader would take such care in removing her photograph from the periodical. Or, perhaps, because of the article’s politely biting tone, the reader omits the text from his or her clipping.

The origin of the clipping established, we work to determine who might have procured this photograph of Helena Paderewski from The Philadelphia Record.

Only three-years-old at the time of the newspaper’s 1902 publication, Paul B. Victorius was probably not responsible for clipping or inserting the image. However, a chance look at Victorius’s genealogical records reveals that his mother, Rose Bandler Victorius (1874-?), was a Polish immigrant. Born in Krákow, Poland, Rose immigrated to the United States as a young child, married New York native Abraham Victor Victorius (1872-1932), and with him raised twins: Jeannette Waldron (1899-1996) and Paul Bandler Victorius. Might Rose, a 28-year-old mother of two young children living (ostensibly) in New York, have clipped this photograph of a musician’s fair wife (and fellow Pole) from the pages of The Philadelphia Record (which in 1902 had “the largest circulation of any newspaper in Pennsylvania”) and preserved it in a book of literary criticism? It’s a stretch, but it does seem plausible.

Might this particular clipping have found its way into this particular text by other means? Of course. Might Paul Victorius have obtained the book through channels other than inheritance? Naturally.

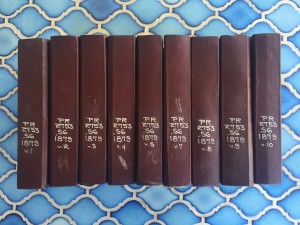

Indeed, Mr. Victorius owned and donated to the University a few, but not many, other books of literature. A search through the Special Collections catalog for books donated to UVA by Paul Bandler Victorius reveals that the vast majority (815 of 844) bear call numbers beginning in QH, denoting Natural History and Biology. The next most populous sections are PR (English Literature) with eight titles, PZ (Children and Young Adult Literature) with three, and PS (American Literature) with two. Due to the limits of the library’s records, these findings represent only those volumes held in Special Collections and exclude books (like this one) that might be part of the library’s greater circulating collection. Given the information we have, however, George Eliot’s Poetry, and Other Studies seems to be an odd, but not wholly unprecedented, component in UVA’s collection of Victorius-related texts.

Determining the connection between Helena Paderewski and Rose Cleveland is a similarly speculative undertaking. Records indicate that Ignacy Paderewski was acquainted with (“on friendly terms with,” even) President Grover Cleveland, as the pianist-turned-diplomat was with nearly every subsequent American President up to, and including, Franklin Roosevelt. Though I was unable to find any evidence of a relationship between the pianist’s wife and the President’s sister, it seems possible that the two women would have been acquainted with one another. Might a reader of the July 8, 1902 Philadelphia Record have recognized, or known of, a connection between Helena Gorská Paderewski and Rose Elizabeth Cleveland? Again, it’s a stretch, but perhaps.

Might the reader have been compelled to insert this particular photo into this particular book because he or she observed that Helena Paderewski, Rose Cleveland, and Mary Ann Evans (known by her pen name George Eliot) were all forceful, female agents? Perhaps. Might the placement of the clipping have been the result of substantially more, or entirely less, forethought? Of course.

The provenance of this text is difficult to determine and the narrative of its modification is incomplete. Even after many hours of research, I cannot report with any certainty how, or why, this particular image arrived in this particular text. As unsatisfying as this in some ways feels, there is gratification in the rich and complex stories that come forth when we ask questions of the historical artifacts that we encounter in our everyday lives, as this book so wonderfully demonstrates.

Sources

Berkowitz, Judith Ann. “Paul Bandler Victorius.” Geni. N.p., 27 July 2015. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

Berkowitz, Judith Ann. “Rose Victorius (Bandler).” Geni. N.p., 29 January 2012. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

“1902 Boston Americans.” BaseballReference.com. FoxSports, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

Feinstein, Lee A. “Ambassador Feinstein’s Remarks.” 150th Anniversary of the Birth of Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Great Assembly Hall, Royal Castle. 6 Nov. 2010. IIP Digital. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

“Frances Cleveland Biography.” The National First Ladies’ Library. Museum/Saxton McKinley House, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

“Freeman Victorius: A UVa Corner Tradition.” Sloan Manis Real Estate Partners. N.p., n.d. Web. 22 Apr. 2016.

“Ignacy Jan Paderewski”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

Madame Paderewski’s Dolls. 1910-1915. The Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C. Flickr. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

“Paderewski’s Wife: A Personality Decidedly Attractive and Refined.” The Philadelphia Record [Philadelphia] 9 July 1902, Womankind sec.: 9. Google News. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

“Paul Victorius Evolution Collection.” Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library. University of Virginia, n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

Phillips, Anna M Laise. “Mme. Paderewski’s Dolls.” The Craftsman XXIX.1 (1915): 114-15. Digital Library for the Decorative Arts and Material Culture. University of Wisconsin. Web. 24 Apr. 2016.

Rose Elizabeth Cleveland, President Grover Cleveland’s Sister and White House Hostess. 1910-1920. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Library of Congress. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

“Some Store History.” Freeman Victorius. N.p., n.d. Web. 14 Apr. 2016.

“Three Cloth Dolls by Madame Paderewski with Original Medals.” Theriault’s: The Dollmasters. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.

“Very Rare French/Polish Cloth Doll by Madame Paderewski with Original Medallion.” Theriault’s: The Dollmasters. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 Apr. 2016.