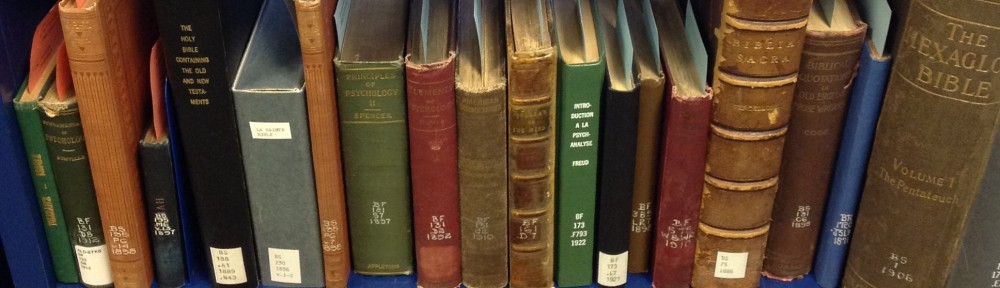

Tucked into the front cover of a copy Mrs. Thomas Bailey Aldritch’s memoirs covering her husband and their shared social circle, Crowding Memories, is an exquisitely preserved note. Though the material of the card and the ink there inscribed are of the highest quality, the quality of the French language text is decidedly lacking. The note reads:

À Mlle Hubbard

Je vous veux tout le bonheur de la saison

de

Kasia Mahoney

To Mademoiselle Hubbard

I want you all of the happiness of the season

from

Kasia Mahoney

Here I have purposefully translated Mahoney’s note in a clunky way to be faithful to the manner in which she wrote her French text. She has made two interesting French errors that allow us to draw conclusions about the nature of her relationship with Hubbard. First, she uses the phrase “je vous veux” which, literally translated in isolation, means “I want you.” What Mahoney probably wanted to say was “je vous souhaite…” which would mean “I want for you,” and better fits the benevolent spirit of her note. Her second error is in signing off with “de,” which, though it does indeed mean “from” and would be used on a “to/from” for a gift as her salutation suggests, is certainly not the way one would sign a letter.

So why the French lesson? Mahoney’s inelegant French, as well as her addressing of the note’s recipient with a formal “Mademoiselle,” suggest that we are most likely looking at a note from a student to a teacher. Though Mahoney’s letter is not linguistically perfect, its earnestness in form and content speak to a certain desire to please a figure of authority.

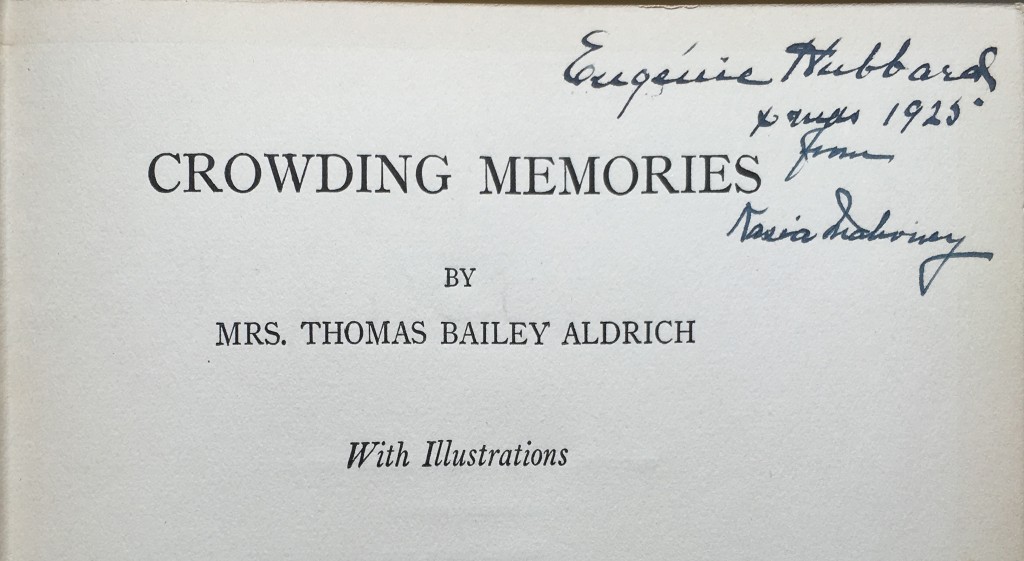

The owner’s signature — in a different hand from the note — on the title page gives us Hubbard’s first name and the date of the gift.

In order to test my hypothesis that Kasia Mahoney was Eugénie Hubbard’s (see how I learned her first name above) student, I had to first identify the two women.

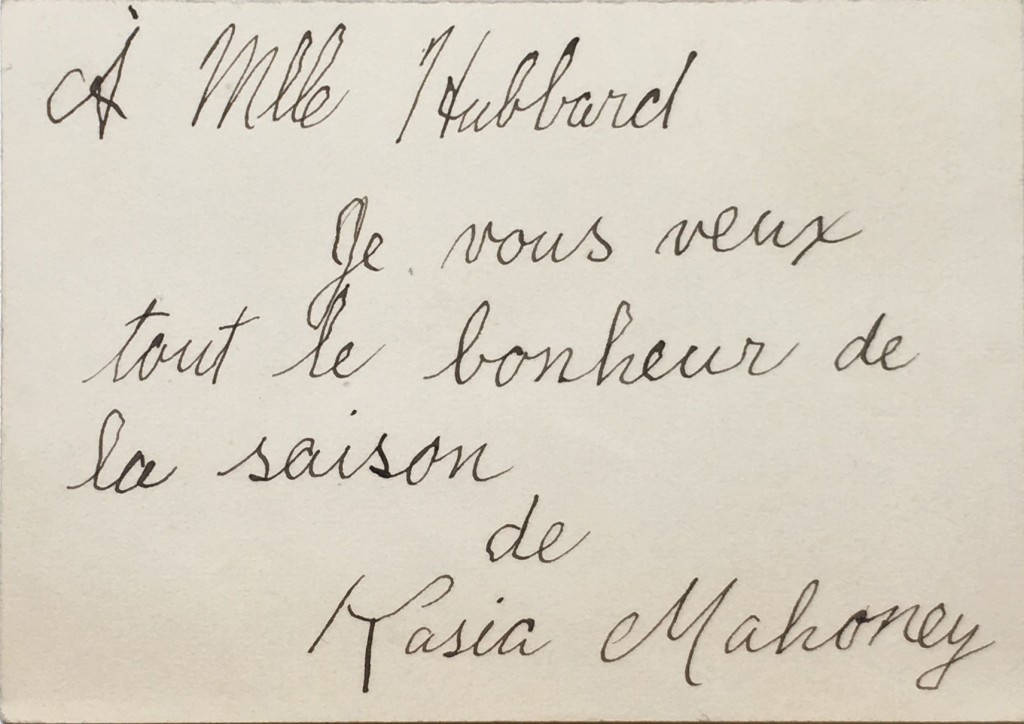

A search for “Kasia Mahoney” turned out to be far more sensational than anticipated. Her name is splashed across front pages from her native to New York, through the Midwest, and even as far away as Utah starting in the year 1927. Here are some of the more choice headlines:

And lastly, Mahoney makes a cameo in the following:

In the articles corresponding to these headlines, we learn just as much about Kasia Mahoney’s jaunt away from her Madison Avenue home as we do about prevailing attitudes towards women in the late 1920s. It is notable that Mahoney, even though she was fifteen when she took flight and was seventeen when the Ogden Standard Examiner article was published, is invariably referred to as a “girl,” even a “small girl.” From our vantage point a century later, doesn’t it seem odd that a fifteen-year-old is characterized as a child even when she lived in an era when lifespans were shorter and child labor laws were less strict?

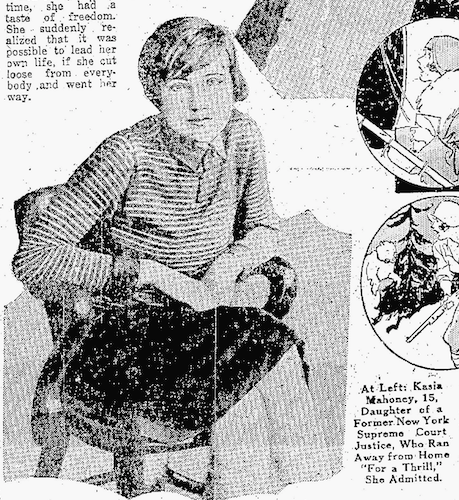

The Ogden Standard Examiner article, from Columbia University’s Professor William M. Marston, clearly delineates the infantilization of these runaway women. First, Marston denies that these women, being mere children, have agency, stating that “such girls may not be aware of their own motives for their actions” and that they are “under the influence of…new freedoms” women had gained at the time. Second, he melds such theories as Social Darwinism and physiognomy to declare that these heiresses’ flights from their tony mansions are inevitable. He compares women to pack animals, observing that “in nature we find the female frequently fending for herself,” and attributes some of the flights to women’s being more “susceptible to comradeship” since their female peers sometimes encourage them to run away. Marston also echoes the phrenological and physiognomical studies of the past century when he conducts a detailed analysis of the Frances Smith in the headlines. He notes that, “judging by her face, she is cautious, shrewd, a commonsense kind of girl” and that “her chin is sharp, which shows that she is an extraordinary woman, in that she can focus her mind resolutely on what she intends to do” — even if, as he writes earlier, she has no idea why she is doing it! Third, he belittles these women as being little more than consumers, hypothesizing that these women had no reason to run away given their social standing and “no unsatisfied desires for clothes.” Lastly, Mahoney, whose likeness appears as an illustration accompanying the article, is even depicted as being childlike: she is shown slouching forward, making her body smaller, and her eyes are enlarged and vacant like those of a young child.

Though Mahoney and her fellow runaways are relentlessly characterized as children in the Marston article, he does touch on something very interesting: the New Woman’s desire to make her own living. Referring once again to Frances Smith, the Professor concludes that “When she got to college for the first time, she had a taste of freedom. She suddenly realized that it was possible to lead her own life…She probably got a job and began living her own life.” This evocation of a desire for an occupation is certainly something applicable to the life of our subject, Kasia Mahoney. In The Bridgeport Telegram headline above, Mahoney is called a “prodigy” and the accompanying article specifies that “She is most studious…a linguist of brilliant ability and possesses talent in writing…She has great confidence in her ability to make a career.” Despite her ambitions at 15, the last Census record we have of her in 1930 still lists her as being a member of her father’s household with her occupation being “none.”

Although we cannot say for sure that Kasia’s ambitions met a dead end or that she ran away in order to “make a career” away from her prescribed heiress lifestyle, these details certainly paint for us a picture of a headstrong, intelligent young woman.

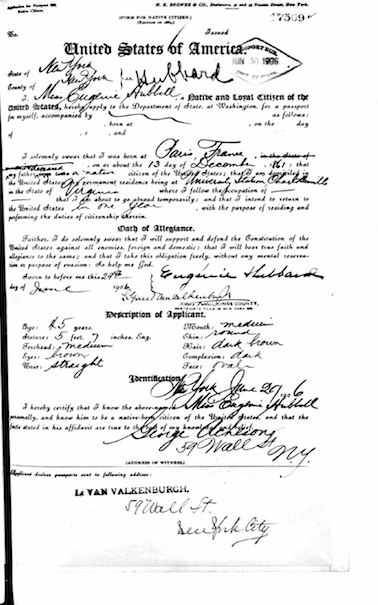

Now, how to tie Kasia’s possible desire to liberate herself to the notecard tucked in Crowding Memories? How to tie her to Eugénie Hubbard? My earlier conclusion that Mahoney was likely the student in her relationship with Hubbard certainly fits well with her reputation as being a linguist of great talent, especially for her age. She would have been thirteen years old when she gifted the book to Mademoiselle Hubbard in 1925, and therefore even her awkward French could have been viewed as an achievement. We have no conclusive evidence that Hubbard was the teacher who led her to such commendable linguistic efforts, but we can surmise that since Hubbard was a native speaker of French and that their age difference was probably too great for them to have been mere friends, she was likely an authority figure for Mahoney. Hubbard’s application for a passport to the United States reveals that she was born in Paris, France in 1861, making her no less than fifty-one years older than Mahoney, and that she immigrated to the United States in 1906 and therefore spent considerable time in France.

What remains unclear is whether Mahoney and Hubbard ever actually met in person. While Hubbard’s passport application was validated in New York, she lists her planned residence as “University Station, Charlottesville.” Indeed, in the 1910 Census, she is listed as being a “relative” and member of the household of L. Bruce Moore in Charlottesville. However, the 1940 Census taken just four years before her death states that, in 1935, her residence was “New York, city.” So it is certainly possible that immediately after her arrival to the United States, she lived in Charlottesville, but somewhere in the window of 1910-1935, she (and her family) relocated to New York City. This window of time makes an in-person gift-giving between the heiress Mahoney and the immigrant Hubbard possible.

To clarify that Hubbard was some sort of teacher-figure for Mahoney, it is important to consider Hubbard’s biography. While Eugénie Hubbard possesses a French name and was born in Paris, her gravestone tells us that her parents were the Americans Daniel and Mary Hubbard. The 1910 Census furnishes the detail that her father, Daniel Hubbard, was born in Louisiana, making it a possibility that he was a native speaker of French and wanted his daughter to be in touch with her francophone roots and raised her abroad. It is also clear that Eugénie, while not as wealthy as Mahoney, came from an affluent background: in a report from the University of Virginia School of Architecture, “Eugenie” Hubbard is noted to have granted the rights to “Howard Place (Mayhurst)” to a new owner. In 2016, this property is known as the Mayhurst Inn, a Civil-War-era “mansion” in Orange, Virginia built by the great nephew of President James Madison and known for having hosted Confederate Generals Robert E. Lee and “Stonewall” Jackson.

Hubbard’s also being a sort of heiress who was never formally employed (as per her Census records and her passport application) leads me to believe that, while she would not have been Mahoney’s teacher in any formal capacity, she may have socialized in similar circles as Kasia’s father Jeremiah Mahoney, making it feasible for her to have been chosen to be an informal conversation partner or tutor for the budding teenage linguist.

Though we can imagine a warm, pseudo-granddaughter/grandmother relationship between thirteen-year-old Kasia Mahoney and sixty-four year old Eugénie Hubbard, there is something slightly subversive when we contextualize their relationship with this gifted book. Crowding Memories was written by Mrs. Thomas Bailey Aldritch and was considered to be a sort of companion book to the official biography of Thomas Bailey Aldritch that was also published in 1920. Mr. Aldritch was known as a consummate man of letters, having published poetry and served as an editor of The Atlantic Quarterly. He had many notable friends and acquaintances including such illustrious figures as Mark Twain. What makes this gift subversive is that this book is not a widow’s glowing biography of her deceased husband, but instead her perspective on all of the “crowd” with whom the couple socialized. While this book was to be the companion book to the husband’s biography, it instead serves as an alternative narrative of the wife’s memories. I am inclined to follow a (purely conjectural) interpretive reading of the transmission of this book from the young Mahoney to the elder Hubbard as not just an acknowledgement of a mutual admiration for Aldritch, but a tacit understanding that they, as heiresses and socialites, also had a perspective worth sharing with the world. They were not “small girls” but instead intelligent women who sought expression in their multilingual, multigenerational friendship. Their memories were not to be lost in the crowd of a society that sought to infantilize them at every turn.

The last piece of the puzzle also demonstrates a sort of subversive femininity. The bookplate of our copy of Crowding Memories specifies that the book was presented to the University of Virginia by “L. Bruce Moore.” This would have been impossible; the man bearing this name has a death certificate that was registered in 1926 and no record of a son bearing his name. How could a dead man present a book that wasn’t even his but that was instead gifted to Eugénie Hubbard, who at that point lived in New York? The answer to this question reveals another enduring female friendship. The presenter of the book, “L. Bruce Moore,” would have to have been his widow, Helen Moore, called “L. Bruce Moore (Mrs.)” in the 1940 Census. With whom did Mrs. L. Bruce Moore live in Charlottesville? With her “sister” Eugénie Hubbard (Hubbard is listed as a “relative” of Helen Moore in 1910). The Alderman Library possesses dozens of books presented under the “L. Bruce Moore” name, several of which coalesce around the theme of young, wealthy women making gutsy moves to big cities. In this collection we see these ingenues move from the Wild West to New York City in Letters Home (1903 edition), from Boston to Venice in William Dean Howell’s The Lady of the Aroostook (1907 edition), from England to The New World in Mary J. Holmes’s The English Orphans (1900 edition), and — perhaps most appropriately of all considering Eugénie’s biography — from New York to The Continent in Henry James’s Daisy Miller (1879 edition). Therefore, even after Hubbard passed away in 1944, traces of her transatlantic voyage and her female friendships with the Americans Mahoney and Moore live on, here for the independent women of 2016 to discover in Alderman Library.

Works Cited

Aldritch, Mrs. Thomas Bailey. Crowding Memories. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, The Riverside Press Cambridge, 1920. Print.

Death Certificate for L. Bruce Moore, 20 Mar 1926, Commonwealth of Virginia, Bureau of Vital Statistics, State Board of Health. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

“Fate Kind to Small Girl, Out to See World.” Chicago Tribune. Chicago, 26 Feb 1927. Web. 11 May 2016. Archives.chicagotribune.com.”Girl Prodigy, 15, Daughter of Supreme Court Judge, Missing.” The Bridgeport Telegram. Bridgeport, Connecticut, 25 Feb 1927. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

Gravestone for Eugénie Hubbard, 1861-1944, Graham Cemetery, Orange, VA. Web. 11 May 2016. Findagrave.com.

“Kasia Mahoney Found, Left Mansion Home for ‘Thrills’.” The Bridgeport Telegram. Bridgeport, Connecticut, 26 Feb 1927. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

Marston, William M. “How the New Psychology Explains Why Frances Smith Disappeared.” Ogden Standard Examiner, Ogden, Utah, 3 Mar 1929. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

Mayhurst Inn: 1859 Virginia Plantation. Mayhurst Inn, 2016. Web. 11 May 2016. mayhurstinn.com.

School of Architecture, University of Virginia. “Howard Place (Mayhurst), U.S. Rt 15, Orange vicinity, Orange County, Virginia, HABS No. VA-1082.” Charlottesville, VA, n.d. Web. 11 May 2016. cdn.loc.gov.

“Thomas Bailey Aldritch.” The Literature Network, 2016. Web. 11 May 2016. online-literature.com.

United States. Census Bureau. “Department of Commerce and Labor– Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, Charlottesville, Sheet No. 19 B.” United States Census 1910. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 4 May 1910. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

United States. Census Bureau. “Department of Commerce – Bureau of the Census, Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940, Population Schedule, Virginia, Charlottesville City, 104-5.” United States Census 1940. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 18 Apr 1940. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

United States. Census Bureau. “Form 55-4, Department of Commerce- Bureau of the Census, Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population Schedule, New York, Manhattan (Districts 501-750), District 546.” United States Census 1930. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 14-5 April 1930. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.

United States. Passport Applications. “Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 – March 31, 1925, 1906-7, Roll 0016 – Certificates: 17289-17998, 28 Jun 1906-08 Jul 1906.” New York: Department of State, 30 June 1906. Web. 11 May 2016. Ancestry.com.