France has always had a problem with what they call l’autre, the Other.

In contemporary history, this trouble with “Otherness” is exemplified by the astonishing number of French citizens who are defecting from their native land in order to join the forces of Daech (the preferred name in French for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, known as ISIS or ISIL). What could possibly make these citizens of one of the most idolized countries on earth join a radical militant group terrorizing the Middle East? To answer this question, many scholars have pointed to a general sense of disenfranchisement among — most notably — young people from immigrant families, particularly those who practice Islam. Stated simply, these at-risk individuals do not feel “French” and do not feel like they are invited to participate in French culture and “Frenchness.” In fact, this detachment from la République has been identified as one of the main triggers of the rash of horrifying terrorist attacks in Paris.

This phenomenon of alienating the Other from French culture is certainly not new. While the United States experiences more cultural fractures on the basis of race, in French history it can be observed that greater fault-lines form on religious grounds. Indeed, the Gallic people have exhibited animosity towards Muslims as early as the eleventh century: The Song of Roland, considered to be the first complete work of literature in the French vernacular, depicts Charlemagne’s Christian army clashing with the Muslim Sarrasins.

Though French antipathy towards Islamic culture is well-known and well-documented, the abiding mistrust of the Jewish people is perhaps less apparent. When we, in the post-World War era, think of antisemitism, we often connect this form of prejudice to Nazism, but it runs deeply and broadly through the entirety of European recorded history.

No event better laid French antisemitism bare than the all-encompassing Dreyfus Affair. When I once told my undergraduate thesis advisor that I wanted to know more about the Affair, she said, “It would take a year or more of graduate seminars to critically understand even the tip of its iceberg.” Therefore, for our purposes, I will simplify it: In 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus was accused of committing the (relatively bureaucratic) crime of transmitting classified French documents to the German Embassy in Paris. It came to light two years later that Dreyfus, who was of Alsatian Jewish descent, had been framed when evidence proved that a more “French” military man, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy, was the true spy. However, Esterhazy was quickly acquitted in a heavily biased military trial while Dreyfus was saddled with additional layers of cover-up charges. One of the most famous dreyfusards (“supporter of Dreyfus”; versus the anti-dreyfusards) arguments came in the form of novelist Émile Zola’s splashy “J’Accuse…!” published on the front page of L’Aurore in 1898, in which he accused the French government of complicity in Dreyfus’s unjust framing. It was not until 1906 that Dreyfus was fully exonerated and allowed to rejoin the military, making the total length of the Affair twelve years. Even with the actual events coming to a close, the scars they left behind would last for decades to come and threaten the very foundation of la République.

Zola’s famous “J’Accuse…!” defending Dreyfus and accusing the government of complicity in his unfair treatment (1898)

Though the details of the Dreyfus’s myriad sentences and the motivations of the players involved are extremely complex, one of the primary contemporary assessments of the Affair is abundantly clear: Dreyfus was considered to be a more appealing culprit for treason on the basis of his Otherness. Because Alfred Dreyfus came from Alsace, a territory that at many points in history had been German, and also practiced a religion that was not French Catholicism, he was Other enough to be the perfect scapegoat for a political scandal.

Even as the Dreyfus Affair threatened to split the whole of French society into dreyfusards and anti-dreyfusards, within each of these factions, shared political views on the Affair forged tight bonds. One of these bonds is preserved in our Book Find, a 1903 volume by Joseph Reinach entitled Histoire de l’Affaire Dreyfus.

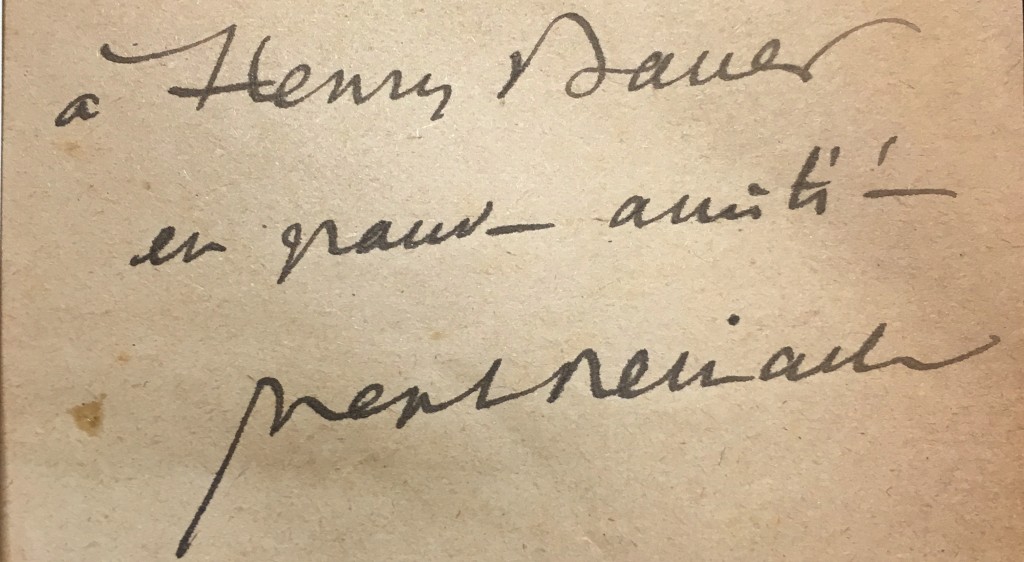

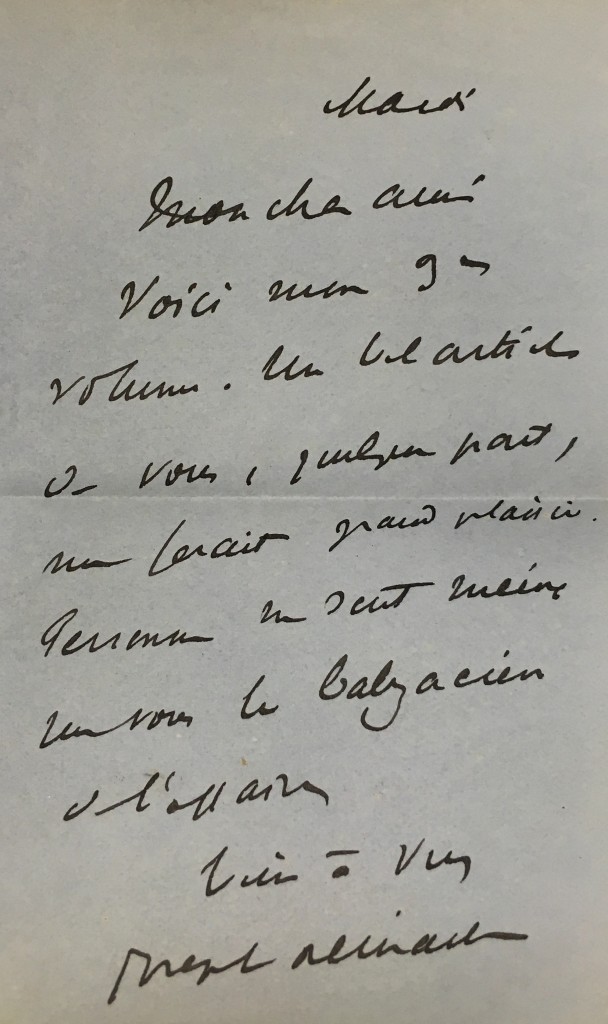

The traces in this book are particularly interesting in terms of format. Even as the gift inscription on the title page is typical, reading “To Henry Bauër, with great friendship, Joseph Reinach,” the meticulous enclosing of the accompanying letter is atypical indeed.

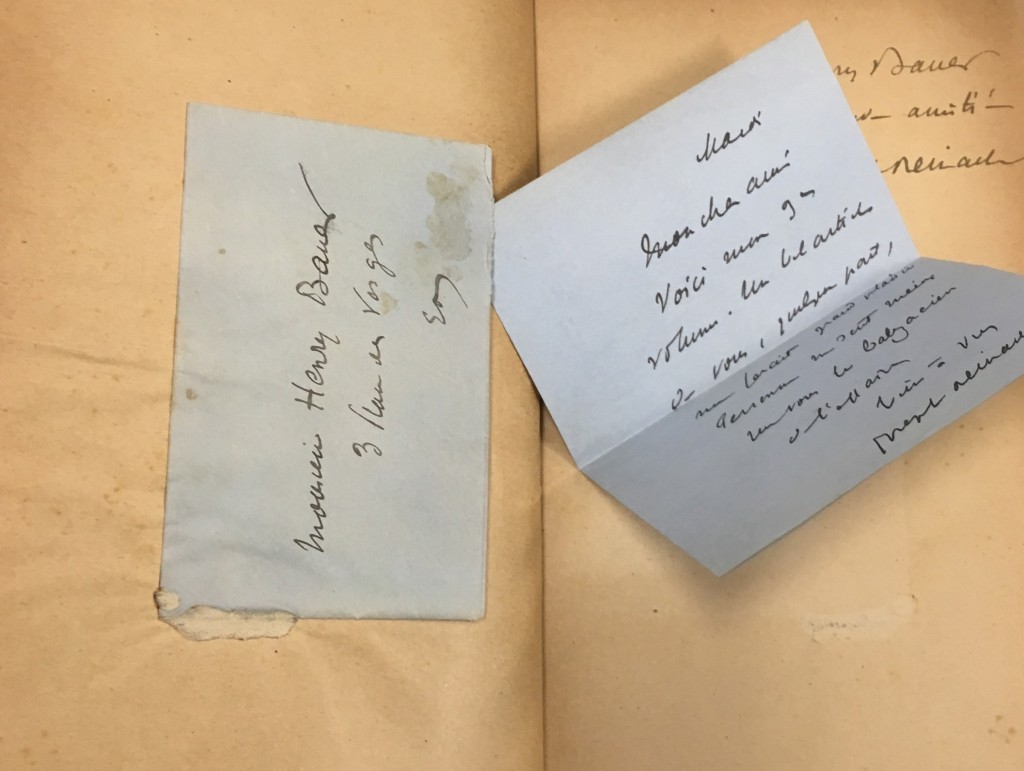

Across from this gift inscription is a remnant of an envelope that has been carefully folded to display the addressee’s residence at the front of a diminutive pocket. Though the envelope was torn, not cut, the resulting paper pocket is crisp and delightfully delicate.

Inside of the origami-like pocket is a note on matching stationery. The paper quality is so fine that the watermarks of “JO” and “EXTRA” are readily visible even without holding the note up to a light source. Once again, we see Reinach’s practically indecipherable scrawl addressing his friend. The note reads:

Lundi

Mon cher ami

Voici mon 9e volume. Un bel article

de vous, quelque part,

me ferait grand plaisir.

Personne ne sait mieux

que vous le balzacien

de l’affaire

Bien à vous

Joseph Reinach

My dear friend

Here enclosed is my 9th volume. A nice article

from you, somewhere,

would please me greatly.

Nobody knows better

than you how to see the Balzac

in the affair

Best wishes

Joseph Reinach (translation my own)

In reading a biography about the recipient, Henry Bauër, I was able to find a transcription of his thank-you note to Reinach:

1er juin 1903

Mon cher Reinach,

Vous me ferez grand plaisir en m’envoyant votre nouveau volume.

Les précédents m’ont ravi. Il me semblait tant était profonde la pénétration des caractères, magnifique la documentation de l’historien, il me semblait assister au développement d’un drame homérique et balzacien dont je n’aurais connu que le scénario.

Vos livres apprennent les ressorts cachés de l’affaire à ceux qui croyaient la connaître le mieux.

Dans les meilleurs sentiments

Je vous serre la main. – H.B. –3, place des Vosges.

My dear Reinach,

You have pleased me greatly by sending me your new volume.

The previous were thrilling. It seemed to me that the insight into the characters was so deep and the historical documentation was so magnificent that I felt as though I was attending the production of a play by Homer and Balzac of which I had, up to this point, only known the synopsis.

Your books teach the hidden motivations of the affair to those who thought they knew it inside and out.

In the best spirits

I shake your hand. – H.B. –3, place des Vosges. (Cerf 87, translation my own)

From this epistolary exchange, we can confirm that Bauër and Reinach were not only personal friends but also political allies that viewed the Dreyfus Affair with a critical eye. These letters show them comparing the historical events to a novel or drama that specifically recalled popular author Honoré de Balzac’s treatment of his characters, who were always neither good nor bad.

Understanding the friendship between Bauër and Reinach by reflecting upon their biographies presents us with an opportunity to begin to understand the often inscrutable Pandora’s box of the Dreyfus Affair.

Henry Bauër has a particularly riveting life story. Born in 1851 in Paris, Bauër was the illegitimate son of none other than literary juggernaut Alexandre Dumas, author of such celebrated classics as The Three Musketeers (1844) and The Count of Monte-Cristo (1844-6). He was the product of a tryst between the celebrated author and the married Anna Bauër, a German woman of Jewish faith. One can imagine that Bauër’s adjacency to fame and a legitimate legacy only served to further demarcate his indelible Otherness. He was not only a bastard child unworthy of his father’s illustrious name, but also Jewish by blood and only half-French by nationality. This muddled identity stood in sharp relief to his half-brother’s illustrious pedigree: Alexandre Dumas fils (“junior”) was twenty years older and would publish his classic novel, The Lady of Camellias, in 1848, when Bauër was only four years old. This novel would later be adapted by Giuseppe Verdi for the libretto of his masterpiece La Traviata, which draws enthralled audiences to this day.

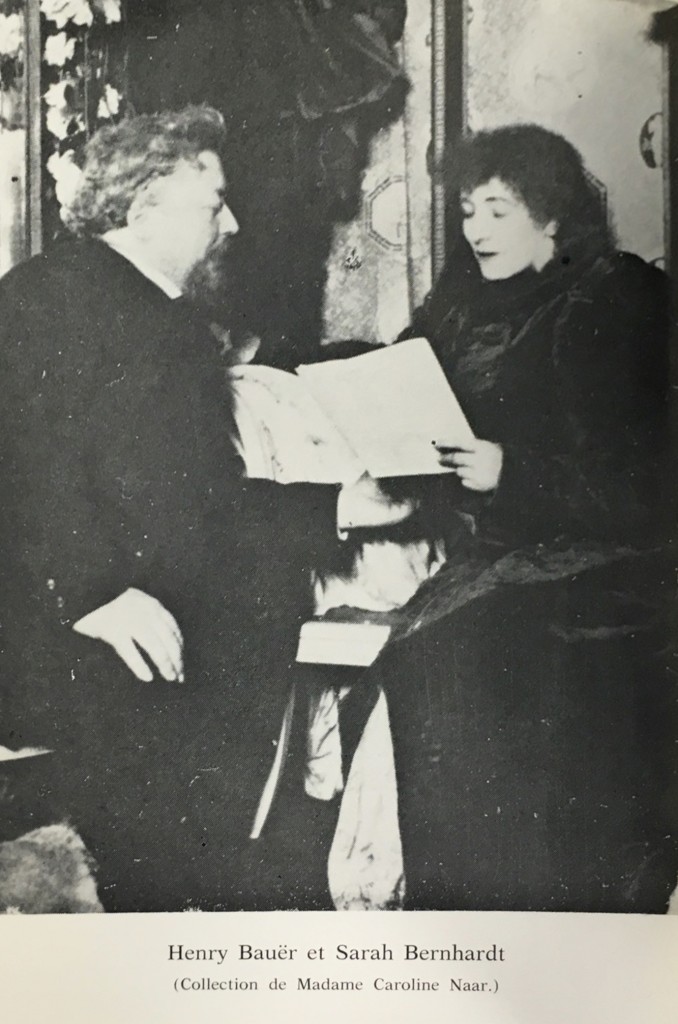

Though Bauër was not a direct descendant of this line of literary masters, he nonetheless found his living in the written word. His biographer Marcel Cerf dubbed Bauër The Musketeer of the Pen in the title of his 1975 examination of Bauër’s life, work, and correspondance. After a youth spent provoking controversy by fighting for the disestablishmentarian Paris Commune of 1871 (which resulted in a period of exile to the archipelago of New Caledonia in the Pacific), Bauër returned to polite society and established himself as a venerable journalist and critic of literature and theater. During his tenure at the paper l’Écho de Paris (“Paris’s Current Events”), he was known for championing Émile Zola’s literary output as well as his dreyfusard work in the political tangle of the Dreyfus Affair.

Bauër’s career as a theater critic enabled him to befriend such individuals as stage superstar Sarah Bernhardt. (Cerf)

However, by the time of Reinach’s gift in 1903, Bauër had left journalism in order to pursue an ill-fated theater career. Since he clearly had not inherited his father and half-brother’s ability to convert writing into a means of making a living, the later years of his life were spent not only in relative obscurity but also in a pecuniary situation that did not befit the son of such an illustrious literary figure.

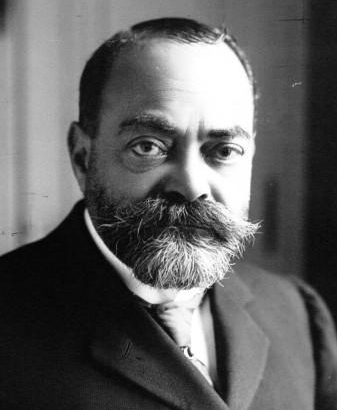

It is during this later, less-successful period that Bauër’s letters reveal that he had begun at least a written relationship with Joseph Reinach. Reinach, born to German Jewish parents in 1856, also worked as a journalist but was primarily known for his political career. Like Bauër, he too experienced a tumultuous career of ups and downs: he served as a Parliamentarian from 1889 to 1898 but did not win re-election largely on the basis of his involvement in the Dreyfus Affair. Reinach is considered to be the champion par excellence of Dreyfus’s innocence. As his gift note to Bauër indicates, Reinach wrote many volumes on the Affair in which he meticulously laid out his argument, in chronological order, that Dreyfus was the victim of an insidious government cover-up. From 1898-9 he wrote no less than eight volumes entitled L’Affaire Dreyfus and subdivided the events of the Affair into thematic units that comprise the volumes. Histoire de l’Affaire Dreyfus, his ninth volume, is the one we possess that was sent to Bauër. Originally published in 1901, it functions as a sort of retrospective on Reinach’s initial Dreyfus series. After the journalistic tear-down of Reinach’s extensive dreyfusard output came to an end, he, unlike Bauër, experienced a renaissance and won re-election to the French Parliament in 1906 – not coincidentally the same year that Alfred Dreyfus was finally pardoned.

Neither I nor Marcel Cerf can pinpoint when or how exactly Bauër and Reinach became friends, but the basis of their friendship as Others in society is abundantly clear. Both men were not truly “French” in that they were of German Jewish parentage. However, given Bauër’s illustrious father and Reinach’s tenacious political career, both men touched fame even in a society that sought to exclude them. Though they never acknowledged in writing that their firm belief in Alfred Dreyfus’s innocence was founded on the fact that he, too, was a Germanic, Jewish Frenchman, it is not difficult to see how they might have identified with the embattled military man.

Even though, at the time of the gift, both men inhabited tony addresses in Paris (Place de Vosges, where Bauër lived, was once the seat of the French royal court and also the home of Victor Hugo; The stationery store indicated on the envelope sent by Reinach is located on the posh Boulevard Haussman, which suggests that he lived nearby), we can make no mistake that they were universally accepted in society. In my search for more information on Joseph Reinach, I came across a truly nasty re-writing of one of his Dreyfus volumes entitled, Joseph Reinach, Historian. The preface of this book, written by Charles Maurras, makes it abundantly clear that the subtitle Historian is intended to be pronounced in snarky quotes: “Historian.” This vicious preface makes it very clear for us that, for many, Jewish writers like Reinach were viewed with contempt. The preface author observes that

“An ardent vital instinct can provide man, particularly of the Semitic variety, with an ersatz approximation of, or even an equivalent to, actual intelligence” (Maurras x, translation my own)

and compares Jews to beasts with instinct, not intellect. Furthermore, he manages to make doubly-racist racist claims about Reinach:

“Mr. Joseph Reinach has gone too far. Never did any Asian sorcerer play as he does with the naïveté of the Gallic people. His example demonstrates that a certain absence of shame can reign over genius and virtue alike” (Maurras xii, translation my own).

Though I was not able to find any such screeds against Bauër, if this is the vitriol with which Reinach, a former Parliamentarian, was vilified, can we even imagine how the bastard Henry Bauër might have fared?

It is in the friendship between Bauër and Reinach, formed on the basis of shared heritage, the Otherness that came with it, and the prejudice they experienced in society despite their notable contributions that we can begin to comprehend the impact of the Dreyfus Affair. On the negative side, we see how the climate in late nineteenth-century France was genuinely hostile to people of different cultural backgrounds and how this undoubtedly played into Dreyfus’s unjust conviction. On the positive side, we see how, in order to brave the waves of antisemitic hatred, French Jews rallied around Dreyfus and formed lasting bonds that allowed them to insist that they, too, were part of the French nation and culture.

Given that this book find provides us with an approachable microcosmic view of a major French historical event, I find this book and its interventions to be of great value. Even though Henry Bauër and Joseph Reinach have largely fallen into obscurity (Indeed, this may be the reason why we have acquired this book here at the University of Virginia and that it has not yet been sent to Special Collections!), through their exchange in this controversial volume, we can begin to decode a historical event that has implications that can help us navigate issues of Otherness in the present day.

Works Cited

Cerf, Marcel. Le Mousquetaire de la plume. La vie d’un grand critique dramatique : Henry Bauër, fils naturel d’Alexandre Dumas, 1851-1915. Paris: Académie d’Histoire, 1975. Print.

Dutrait-Crozon, Henri. Joseph Reinach historien. Révision de l’Histoire de l’Affaire Dreyfus, préface de Charles Maurras. Paris: Savaète, 1905. Print.

El Gammal, Jean. Joseph Reinach et la République (1856-1921). Bulletin du Centre d’histoire de la France contemporaine, vol. 4, 1983, p. 65-70. Print.

Maurras, Charles. Preface. In Henri Dutrait-Crozon. Joseph Reinach historien. Révision de l’Histoire de l’Affaire Dreyfus, préface de Charles Maurras. Paris: Savaète, 1905. Print.

Reinach, Joseph. Histoire de l’Affaire Dreyfus. Paris: Charpentier et Fasquelle, 1903. Print.