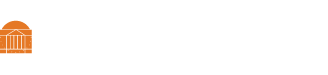

Post by UVA English Department research assistant Maggie Whalen.

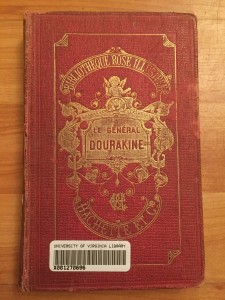

In the weeks following our post on the UVA Library Collection’s many literary treasures tied to Albemarle County’s historic Rives family, UVA community members brought to our attention a few other Rives-owned and -annotated volumes worth investigating.

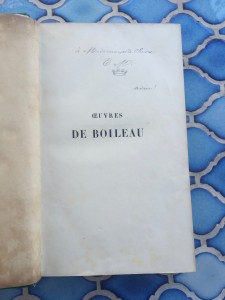

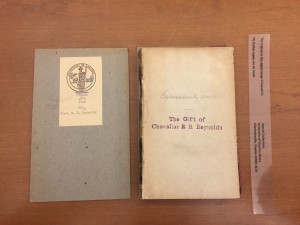

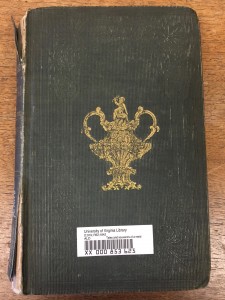

First: an 1853 copy of C. A. Sainte-Beuve’s Oeuvres de Boileau.

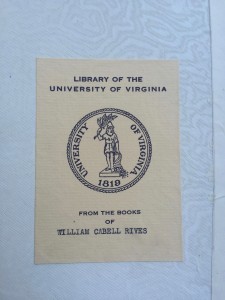

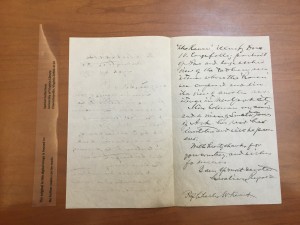

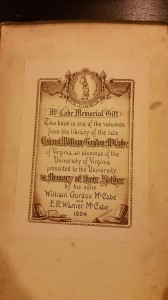

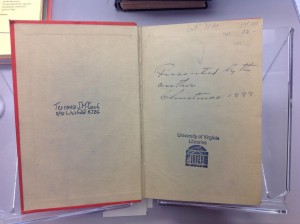

A bookplate in Oeuvres de Boileau indicates that this text came to the UVA Library Collection through the books of William Cabell Rives.

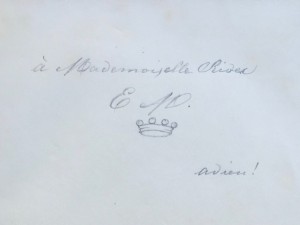

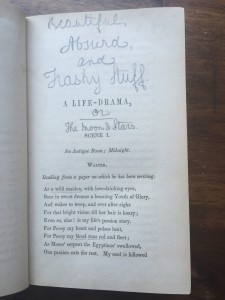

The book is of interest to the Book Traces @ UVA project first for its gift inscription. The note, which appears in pencil on the book’s title page, reads: “À Mademoiselle Rives / E M / Adieu!” Below the gift-giver’s initials is a sketch of a crown.

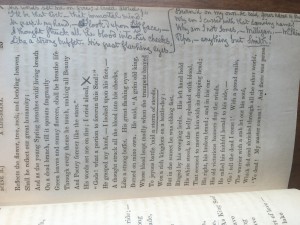

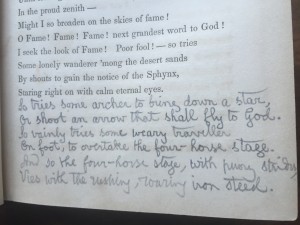

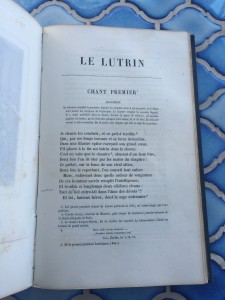

Of further note are the annotations, bracketing, and underscoring of the book’s contents. As its title suggests, Oeuvres de Boileau, or Works of Boileau, contains a number of works by the 17th-century French poet and literary critic Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux. The volume’s contents are organized by genre, among them: satire, epistle, ode, epigram, and poetry.

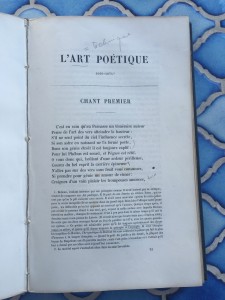

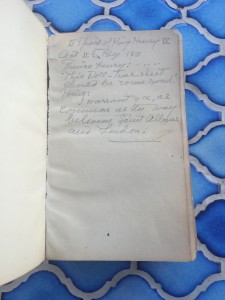

Though marginalia crops up throughout the thick volume, its most heavily annotated sections are those for which Boileau is best known: his still-studied treatise on the rules of Classical verse L’Art poétique (1674) and his mock-heroic epics Le Lutrin (1666). Nearly every page of these two sections contains marks made by a previous reader: brackets, dots, notes in French, and translations in English.

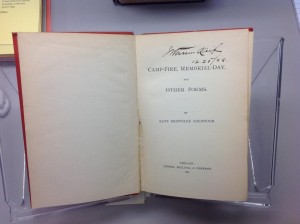

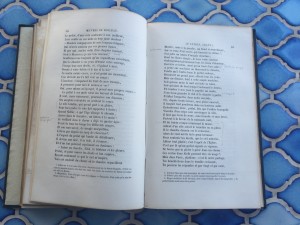

Annotations of Boileau’s L’Art poétique.

Annotations of Boileau’s L’Art poétique.

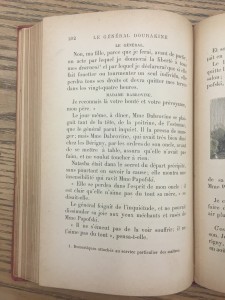

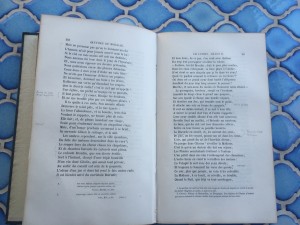

Annotations of Boileau’s Le Lutrin.

Annotations of Boileau’s Le Lutrin.

To which Mademoiselle Rives did this well-marked volume belong? And by whom was it given? A look at the Rives family’s history hints at an answer.

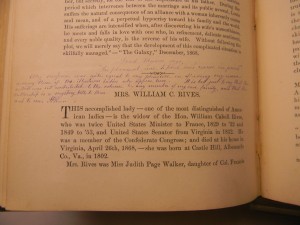

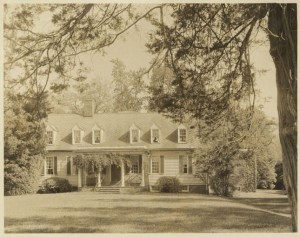

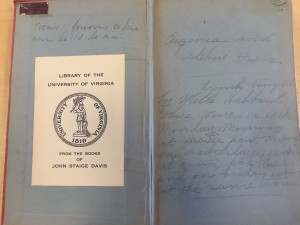

As mentioned in our previous post, William Cabell Rives (1793-1868), a wealthy Albemarle landowner and an influential American politician, served twice as the U.S. Minister to France. In the final year of Rives’s first term, 1829-32, his wife, Judith Page Rives, gave birth to the family’s fourth child and first daughter. She was named Amélie by her godmother, then-Queen of France, Marie-Amélie. Shortly after the birth of Amélie Louise Rives, the Rives family returned to the United States. William Cabell Rives served three terms in the United States Senate before he accepted a reappointment as the Minister to France. He served his second term, 1849-1853, under France’s final monarch: Napoleon III. As in his first term, Rives was accompanied in Paris by his family. Indeed, letters preserved in UVA’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library reveal that William’s wife and three youngest children, Alfred (1830-1903), Amélie Louise (1832-1873), and Ella (1834-1892), all resided in France during his tenure as minister.

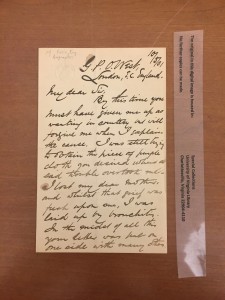

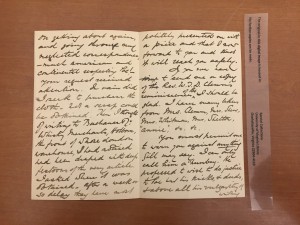

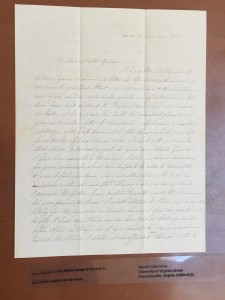

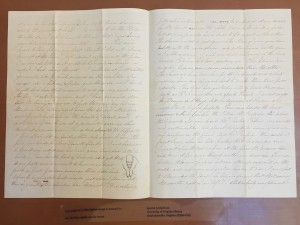

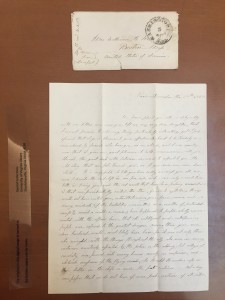

Correspondence between Amélie Louise (Paris) and her sister-in-law, Grace (Boston).

Correspondence between Amélie Louise (Paris) and her sister-in-law, Grace (Boston).

Brown, Alexander, et al. Papers of the Rives, Sears and Rhinelander Families.

Bearing this in mind, it seems possible that this book, published in Paris in 1853, the final year of Rives’s term, might have been a parting gift (“Adieu!”) from French Queen Eugénie de Montijo (“E M,” the crown) to one of Rives’s unmarried daughters (“Mademoiselle”), Amélie Louise or Ella.

Based on the limited biographical information available on the two sisters, it seems possible that either might have happily accepted a text on poetic technique. As discussed previously, the Riveses were a family of writers. Both of the girls’ parents, Judith Page and William Cabell Rives, were published authors. Amélie Louise, who would have been 21-years-old in 1853, dabbled in writing, penning but never publishing a number of poems and stories. 19-year-old Ella seems to have been intellectually inclined, too. In an 1851 letter from the girls’ mother to their sister-in-law, Judith describes Ella passing her time in Paris “surrounded with her grammars, dictionaries, [and] maps.”

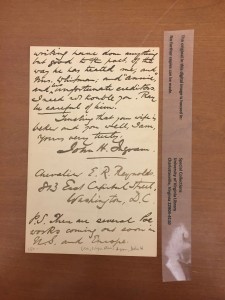

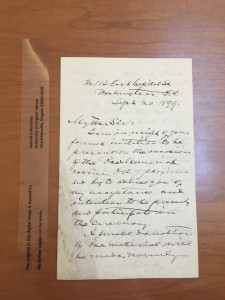

Correspondence between Judith Page (Paris) and her daughter-in-law, Grace (Boston).

Brown, Alexander, et al. Papers of the Rives, Sears and Rhinelander Families.

Unfortunately, records of the queen’s autograph do not confirm this loosely founded hunch and the book’s provenance remains a mystery.

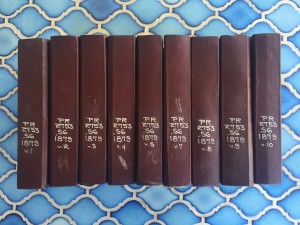

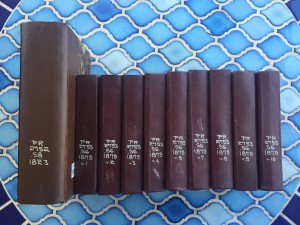

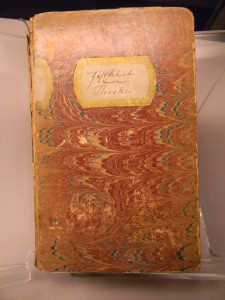

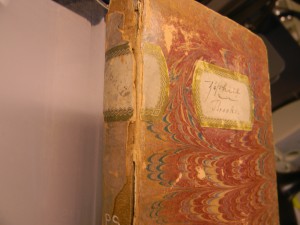

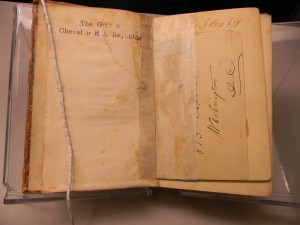

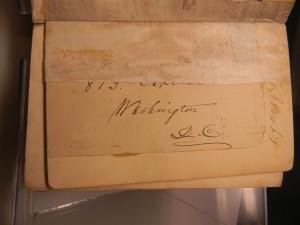

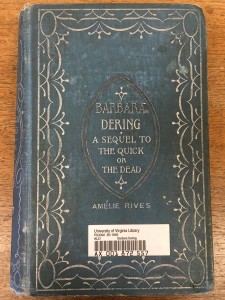

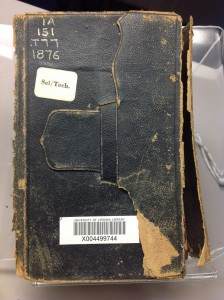

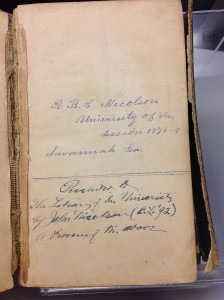

Fast forward 30 years and we arrive at our next subject: The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare, a ten-volume set published in London in 1879.

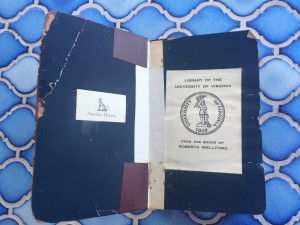

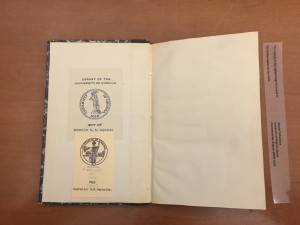

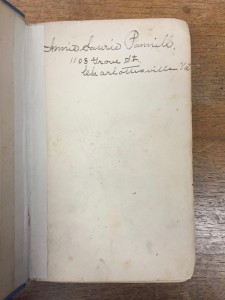

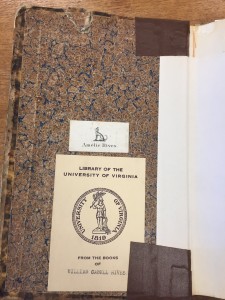

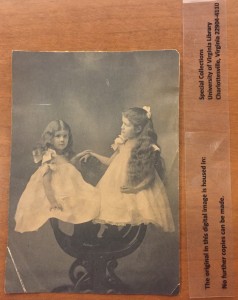

UVA-administered bookplates reveal that the set came to the UVA Library Collection through the books of one Roberta Welford (1873-1956), a women’s rights advocate and suffragist whose papers are preserved in UVA’s Special Collections Library. Personal bookplates indicate that the set was previously owned by Amélie Rives Troubetzkoy (1863-1945), the niece of aforementioned Amélie Louise and Ella, the daughter of Alfred.

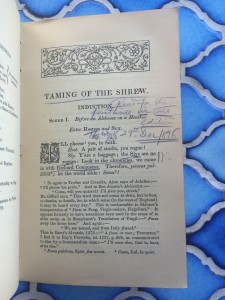

In our first post, we discussed at length another tome of Shakespeare owned and annotated by the second, and most famous, Amélie. That text, a hefty volume entitled The Plays of William Shakespeare, was published in London in 1823. It contains two inscriptions by Amélie, one from 1885 and another from 1890, as well as a number of marginal annotations. Two Gentlemen of Verona, Much Ado About Nothing, Taming of the Shrew, and All’s Well That Ends Well are among the plays most thoroughly marked in this previously discussed text.

The Plays of William Shakespeare. London, 1823.

Considering the substantial overlap in content between these two collections, it’s somewhat surprising that Amélie owned, let alone read and marked, both.

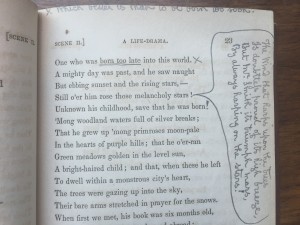

And yet, Amélie’s The Dramatic Works of William Shakespeare is similarly rich with annotations. Of the ten volumes to the set, I was able to examine nine (volume 6 was missing) and found some degree of user modification in each.

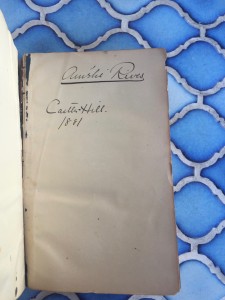

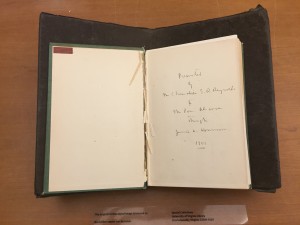

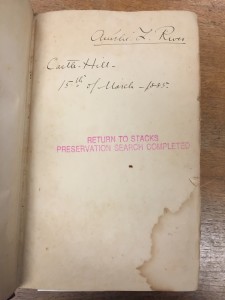

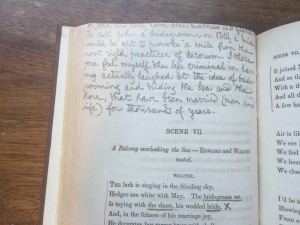

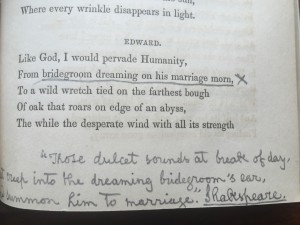

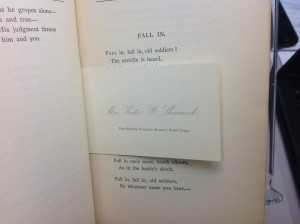

Oddly enough, volumes 7 through 10 are the only texts that feature user inscriptions. All read: “Amélie Rives / 1881 / Castle Hill,” indicating that Amélie acquired this set four years prior to her bulkier edition of Plays.

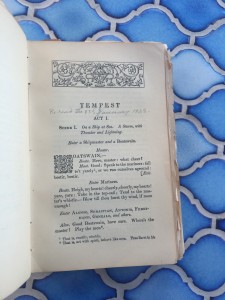

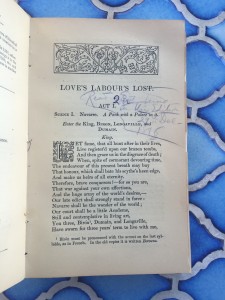

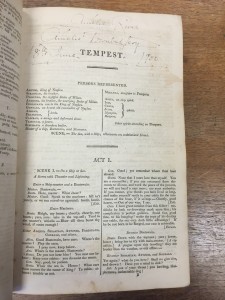

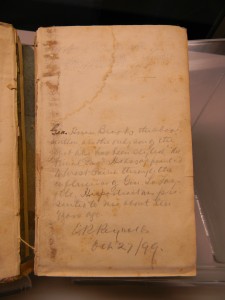

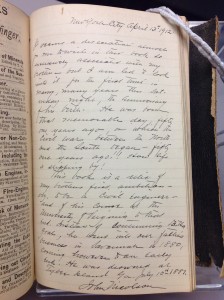

A number of other dates crop up throughout Dramatic Works, particularly on plays’ title pages, revealing that Amélie returned to this text many times throughout her life. She records, for example, that she read Taming of the Shrew “for the first time in this edition the evening of” December 29, 1896; Love’s Labour’s Lost for the “2nd time” on the same night; and “reread” The Tempest on January 23, 1932.

These annotations recall a note Amélie makes in her copy of Plays, in which she records that she read The Tempest, perhaps for the first time, in 1900 at her family’s estate, Castle Hill.

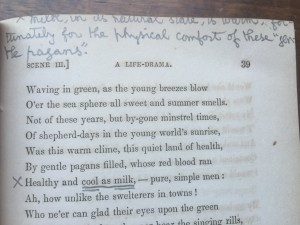

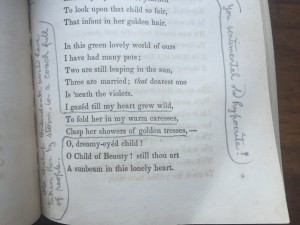

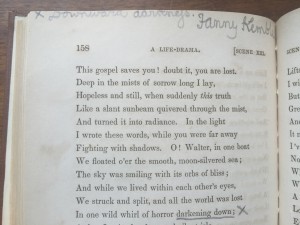

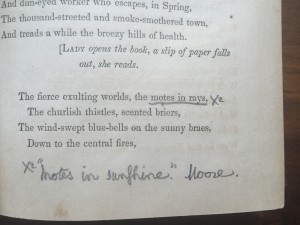

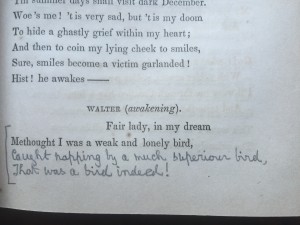

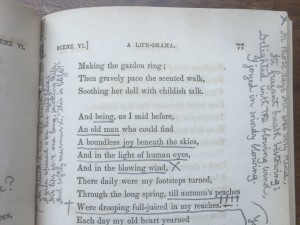

The pages of Amélie’s Dramatic Works are thoroughly underscored and bracketed. Her marginal annotations frequently mention her daily life in Virginia and occasionally reference her own writings.

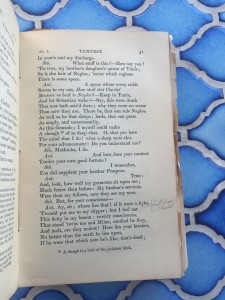

Annotations in The Tempest. In the first image, she marginally defines “kybe” as a “chilblain.” In the second, she underscores “homely” and writes: “NB Homely used here as we Virginians use it now!!”

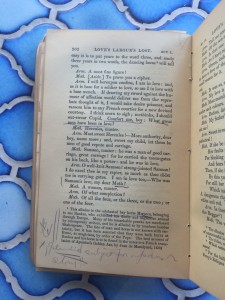

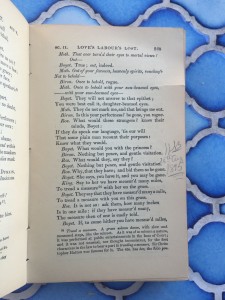

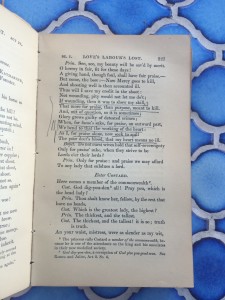

Annotations in Love’s Labour’s Lost. In the first image, Amélie emphatically brackets and underscores a footnote about a famous bay horse named Morocco and writes: “NB Splendid subject for a poem or story!!” Second: she underscores “canary” (a popular dance in Shakespeare’s time) and writes in the margins: “NB Can this be the origin of the Negro ‘pull Cary’?” Third: a marginal note: “NB 25th Aug 1895.” Fourth: some dense underscoring.

Annotations in Troilus and Cressida. Amélie underscores “placket” and writes: “Modern American i.e. ‘Skirt.'”

Annotations in King Lear. She responds to Shakespeare’s use of “nuncle” (defined in the footnotes as “a familiar contraction of mine uncle”), and writes in the margins: “And in Virginia we always address old Negros as ‘Uncle’ + ‘Aunt’ — 1892.”

Annotations in the Preliminary Remarks to Macbeth. Amélie underlines and brackets this passage heavily. She writes extensive, barely legible, notes in the margins. At the bottom of the page, she underscores the name of the author and writes of his book of lectures: “Get at once if possible! ’92.”

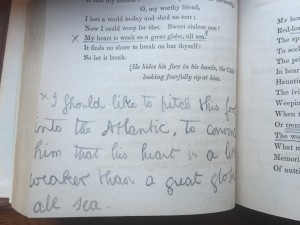

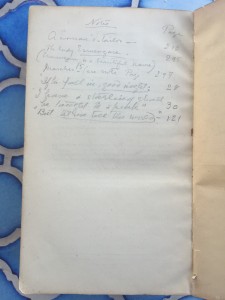

On the final endpapers of several volumes, Amélie collects her favorite lines, passages, phrases, and ideas.

On the rear endleaf of volume 1, Amélie records the following line from The Tempest: “The red plague rid you for learning me your language. Page 214.”

In the final pages of volume 5, Amélie records a series of “Notes” and corresponding “Page” numbers from The First Part of King Henry IV and King Henry V. One note reads: “The lady Ermengare. (Ermengare is a beautiful name.)” On the next page, Amélie transcribes an exchange between Prince Harry and Pions from The Second Part of King Henry IV. The page, however, is torn.

And for that reason, perhaps, she transcribes the passage again on the book’s front endpaper.

On a rear endpaper in volume 7, she copies the following line from Troilus and Cressida: “‘This I presume will wake him’–Page 198.”

In volume 9, she notes perceived “Repetitions of Shakespeare:” “In Hamlet, ‘Himself the primrose way of dalliance treads.’ In Macbeth, ‘that go the primrose way to the everlasting fire.'”

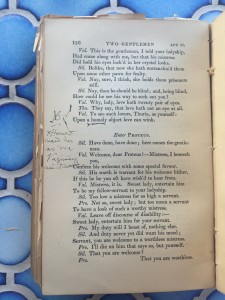

Finally, in volume 10, she writes: “Othello ‘Goats + Monkeys!’ see page 119.” On the corresponding page, Amélie has written “NB” beside the line: “You are welcome, sir, to Cyprus.–Goats, and monkeys!” At the bottom of the page, she brackets a footnote that explains the “great art” of the line.

Perhaps most intriguing among Amélie’s many annotations are those that speficially reference her writing process. In Plays, Amélie marks a line from All’s Well That Ends Well (“So there’s my riddle, One, that’s dead, is quick”), which corresponds to the title of her most famous novel (The Quick or the Dead?). In Dramatic Works, she reads the story of a legendary horse and notes that it would be a “splendid subject for a poem or story!!” Bearing these instances in mind, the endleaf lists explored above read almost like condensed catalogs of potential literary inspiration.

From Judith Page Rives’s The Living Female Writers of the South, to her daughter’s Oeuvres de Boileau, to her granddaughter’s various collections of Shakespeare’s plays, evidence of the Rives women reading with pencils in hand spans three generations and at least 80 years. Though the Rives women are remembered first and foremost as prolific writers, their active engagement with these texts reveals that they were also ambitious readers. As is demonstrated by this post and the last, the UVA Library Collection is dense with examples of the Rives family’s involvement with literature, both public and personal in nature.

Sources

Boileau Despréaux, Nicolas, and Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve. Oeuvres : Avec Notes Et Imitations Des Auteurs Anciens. Paris: Furne, 1853.

Brown, Alexander, et al. Papers of the Rives, Sears and Rhinelander Families. Accession #10596, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2016. Web. 18 Mar. 2016.

Hall, Fitzedward, et al. Letters of the Rives Family. .

“Nicolas Boileau”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

Papers of Roberta Wellford, Accession #6090, Special Collections Dept., University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, Va.

Rives Family Papers Compiled by Elizabeth Langhorne, 1839-1990, #10596-d, Albert H. and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va.

Rives, James Childs. Reliques of the Rives (Ryves). Lynchburg, Va.: J. P. Bell Co., 1929.

Shakespeare, William, and Samuel Weller Singer. The Dramatic Works. 3rd ed. rev. London: G. Bell, 1879.

Shakespeare, William, et al. The Plays of William Shakespeare. New ed. London: Printed for F. C. and J. Rivington; [etc., etc.], 1823.