Guest post by Tessa Berman.

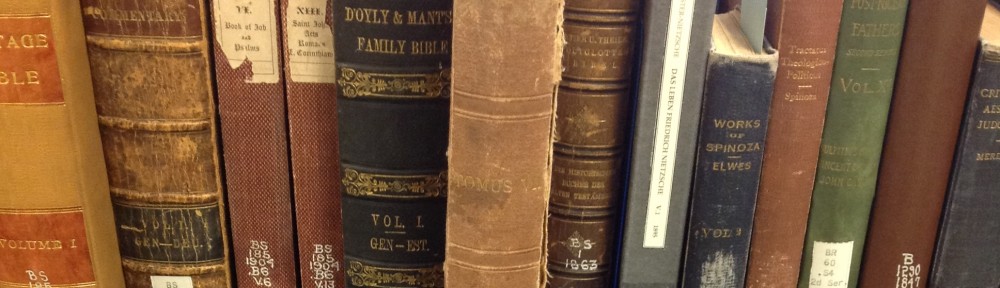

Unassuming in appearance, a time-worn book with a featureless brown cover circulates through the library system of The University of Virginia. Within its pages, the book offers modern readers a breadcrumb trail of marginalia that, if adventurously followed, charts a passage through the Victorian Period and into the modern day. Published in 1841, the book, Poetical Works of Miss Landon, passed through many hands and illustrates the Victorian habit of making personal connections with texts through handwritten annotations (Figure 1). The collection of poetry was written by Letitia Elizabeth Landon. A popular and prolific writer, she was beloved by the people of her time. This hardcover traveled through four generations of the Slaughter family and offers a peek into the thoughts and lives of those along its journey.

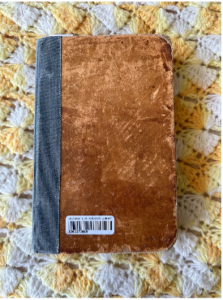

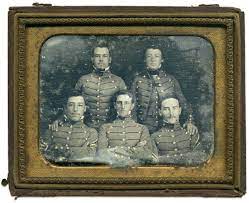

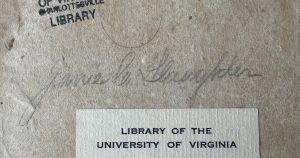

To fully understand the path this book traveled and the personal connection its readers had to the text within, we must start at the beginning. Published in 1841, this copy of Poetical Works of Miss Landon was first owned by Dr. Thomas Towels Slaughter (1804-1890) and his first wife, Jane Madison Chapman (1806-1852). Thomas’s ownership inscription appears prominently on the back free end paper (Figure 2). “Thomas” appears at the top of the page followed by a full signature, “Dr. Thomas Slaughter” across the center page. Below the pencil signature is the name “Madison”, the maiden name of his first wife. Married in 1828, Thomas and Jane had twelve sons together (FamilySearch.org). On page 213 of the text, in the same hand as Thomas’s signature, we find the note, “Lt Col PP Slaughter” (Figure 3). Why did Thomas write this name on this particular page? To answer this question, we must first discover who Lt. Col. P.P. Slaughter was. Born in 1834, Philip Peyton Slaughter was the fifth son of Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter and Jane Madison Chapman (Figure 4) (“Col. Philip Peyton Slaughter, (CSA)”). Philip attended the Virginia Military Institute, graduated in 1857 with the rank of 1st Captain, and went on to serve as a Confederate soldier in the American Civil War (VMI Archives Historical Rosters: Philip Peyton Slaughter). By including his son’s rank title (Lieutenant Colonel) in his note, Thomas places the annotation at a specific point in time. Philip was named Lieutenant Colonel of the 56th Virginia Infantry Regiment in September of 1861. Later, he was appointed Colonel of the same regiment in October of 1863. It follows, this annotation would have only reflected an accurate description of his son between the years 1861-1863. This time frame is significant for the father and son as well. In June of 1862, Lt. Col. P.P. Slaughter was gravely injured at the Battle of Gaines’ Mill (“Gaines’ Mill”). Although he survived his injuries, he would never be able to return to active duty.

Figure 2: Signature of Dr. Thomas Slaughter

Figure 3a: Handwriting comparison between Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter’s signature and the annotation on page 213

Figure 3b: Handwriting comparison between Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter’s signature and the annotation on page 213

Figure 4: Philip Peyton Slaughter as a VMI cadet pictured in front row center taken in 1853 (Gomez)

Thomas inscribed his son’s name on a page titled “Classical Sketches”, above the section “Bacchus and Ariadne”. On this page, two speakers are discussing a painting of the moment the classical Greek figures, Bacchus (God of wine) and Ariande (Princess of Crete), meet during the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. The conversation between the two speakers moves to discussion of the myth itself. Perhaps it is here that Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter’s thoughts linked the text to his son:

LEONARDI: She was the daughter of a Cretan

King-

A tyrant. Hidden in the dark recess

Of a wide labyrinth, a monster dwelt,

And every year was human tribute paid

By the Athenians. They had bow’d in war;

And every spring the flowers of all the city,

Young maids in their first beauty – stately youths,

Were sacrificed to the fierce King! They died

In the unfathomable den of want,

Or served the Minotaur for food. At length

There came a royal Youth, who vow’d to slay

The monster or to perish! – Look, Alvine,

That statue is young Theseus.

ALVINE: Glorious!

How like a God he stands, one haughty hand

Raised in defiance!

(Poetical Works of Miss Landon 213, hereafter cited as PWML)

Like Theseus, Thomas’s son left home to protect the innocents of his state. Lt. Col. P.P. Slaughter raised his hand in defiance, choosing to fight what he may have believed to be the beast of northern aggression. Theseus’s courage to fight for those who could not fight for themselves could have reminded Thomas of the courage he witnessed in his own son when Philip volunteered to join the Confederate Army.

Sadly, we cannot know for sure what Thomas was thinking, as he only left the name of his son as a souvenir of his private thoughts on that day. Maybe the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur was simply a favorite of his son. Or it is possible that the page placement of his annotation was completely random…the page he happened to be reading when his thoughts wandered to his son. Philip was seriously injured in June of 1862 while he was a lieutenant colonel. By this point, Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter had already suffered the loss of eight of his 16 children, one of which died only six months prior to Philip’s injury (FamilySearch.org). Perhaps Thomas was simply driven to distraction while he was reading. As a doctor, he would have understood the gravity of his son’s battle injuries and would have most certainly wished to be able to help him.

After belonging to Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter and his first wife, Jane Madison Chapman, this copy of Poetical Works of Miss Landon passed through at least two hands in the next generation of Slaughters. The names of Eugenia Taylor Slaughter (1842-1929) and Jane Chapman Slaughter (1860-1951) also appear in the book. Ultimately, it was Eugenia’s granddaughter, Lucy Slaughter Stumpf (1923-2000) that donated the book to the library of the University of Virginia (Landon). However, the name of Eugenia’s son (Lucy’s father) never appears in the book. This fact, in combination with the placement of Eugenia’s signature directly below that of the book’s original owner’s name, suggests that the book came into her possession before being passed to Jane Chapman Slaughter.

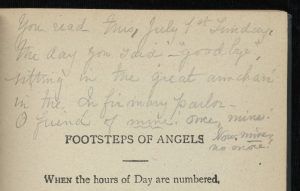

Jane Chapman Slaughter was the daughter of Dr. Thomas Towles Slaughter and his second wife, Julia Rankin Bradford (1823-1892) (“Jane Chapman Slaughter, Phd in French”). Her ownership inscription appears on the inside of the front cover of the book (Figure 5). Jane was an academic. She attended The College of William and Mary for her undergraduate and master’s work. She then became one of the first women to earn a Ph.D. from the University of Virginia, tying the Slaughter family history to the school (“A Guide to the Papers of Jane C. Slaughter”). Like her father before her, Jane left physical evidence of her interaction with this copy of Miss Landon’s poetry. However, her marginalia allow us a much greater window into her emotional interaction with the text. Jane Chapman Slaughter was inspired to add an entire stanza of her own poetical writing to the end of one of the book’s poems (Figure 6)!

Figure 5: Signature of Jane Chapman Slaughter

Figure 6: Additional four-line stanza of poetry added by Jane Chapman Slaughter

Nestled in a section simply labeled “Miscellaneous Poems”, a short work titled “Mardale Head” speaks to the longing and pain of lost love. The poem consists of four, four-lined, stanzas. The first three open with the repeating phrase, “Weep for the love” followed by various descriptions of failed love that the author entreats the reader to feel sadness for: forbidden fate, resigned hope, loving too much in vain (Landon 292-293). The final stanza breaks with this pattern:

Weep for the breaking heart condemn’d

To see its youth pass by,

Whose lot has been in this cold world

To dream, despair, and die.

(Landon 293)

It is likely that the melancholic and defeated tone surrounding the concept of love resonated with Jane, the fourth stanza specifically. In her lifetime, Jane Chapman Slaughter never married or had children. She, too, may have felt her youth pass her by.

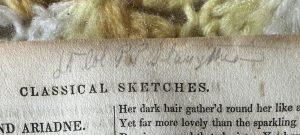

It is within the added stanza of her own creation that offers clues that suggest this poetic expression was tied to a specific time in Jane’s life following a failed romance. She wrote:

Weep for her whose lot is cast

Upon some distant shore

Whose heart is pining for the home

She never shall see more

Jane maintained the rhyme scheme and syllabic format of the original poem, but she changed the subject completely. Her writing does not address “love” as a concept but rather a specific person who is pining for a lost love, likely herself. She felt compelled to adjust the poem of loss in love to specifically represent her personal experience of loss. This annotation becomes a conversation of intertextual marginalia with another book owned by Jane titled, Poems and Ballads by Longfellow. Andrew Stauffer, Professor of English at the University of Virginia, uncovered a diary or sorts within the pages of the 1891 collection (Stauffer). In that book, Jane left dated excerpts outlining a courtship with a man named John H. Adamson and her obvious fondness for him. She also recorded the end of the relationship. Adamson left the country on “crusade” to the West Coast of Africa and never returned. Professor Stauffer determined that some of Jane’s annotations in the copy of Longfellow were written during the relationship in 1900, while some were written years later in reflection as an older woman (Figure 7). Perhaps the stanza she added to “Mardale Head” came somewhere in between these times. Jane writes that her “lot is cast / upon some distant shore” and that her “heart is pining” for a home (her love) “She never shall see more”. This suggests that at the time the stanza was written, Jane’s love had already left her for the literal distant shores of Africa, but she is still pining so the loss is fresh. Jane Chapman Slaughter’s adaptation of this poem exemplifies the practice of Victorian readers interacting with printed text in an intensely personal way.

Figure 7a: Annotations made by Jane Chapman Slaughter at two different times in her Longfellow (a) compared to the stanza written in her Landon (b)

Figure 7b: Annotations made by Jane Chapman Slaughter at two different times in her Longfellow (a) compared to the stanza written in her Landon (b)

Upon Jane Chapman Slaughter’s death in 1951, her books were donated to the library of the University of Virginia but Poetical Works of Miss Landon was not among them. Instead, it found its way into the hands of Lucy Slaughter Stumpf. Perhaps Jane chose to pass this book on during her life to her great-niece because the signature of the girl’s grandmother, Eugenia Taylor Slaughter, can be found in the back of the volume. Eventually, the book did leave the many hands of the Slaughter family. Lucy donated the book to Jane’s alma mater on November 9, 1960. This copy of Poetical Works of Miss Landon now circulates through the hands of students and would-be poets searching for connections and sometimes leaving clues of their own.

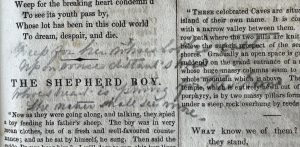

Separate from the written word annotations found in this book, it has also acquired several silent insertions across time. Among these is a stain from a pressed flower and the crumbling residue of its sepal on a page of a poem that speaks about fallen warriors (Figure 8). Without accompanying written information, we cannot know when or where this flower came from, other than that its inclusion predates the book’s donation. This flower belonged to a Slaughter. Perhaps Thomas chose to press a flower from his father’s gravesite on this page as his father was a soldier. Also found among the book’s pages is a heavily underlined passage littered with checkmarks and marked by a paper scrap bookmark fashioned from the edge of dot matrix printer paper, commonly used in the 1980s and 90s (Figure 9). Perhaps a student at the university used the Slaughter copy of Landon to complete a homework assignment on Victorian writers! This copy of Poetical Works of Miss Landon contains a rich recorded history of its readers throughout time and is even connected to another collection within the University of Virginia’s library system. This discovery highlights the importance of genealogical cross-referencing between collections.

Figure 8: Remnants of a dried flower

Figure 9: Underlinings marked by a paper scrap bookmark made of dot matrix printer paper commonly used in the 1980s and 90s

Works Cited

“A Guide to the Papers of Jane C. Slaughter 1809-1951 Slaughter, Jane C., Papers 3700, -a, -b.” n.d. Ead.lib.virginia.edu. Accessed April 27, 2023. https://ead.lib.virginia.edu/vivaxtf/view?docId=uva-sc/viu03349.xml.

“Col. Philip Peyton Slaughter, (CSA).” Geni_family_tree, 2 May 2022, www.geni.com/people/Col-Philip-Slaughter-CSA/6000000052235104347?through=6000000175859298080#/tab/source.

FamilySearch.Org, ancestors.familysearch.org/en/M8N3-4L5/dr.-thomas-towles-slaughter-sr.-1804-1890. Accessed 23 Apr. 2023.

“Gaines’ Mill.” American Battlefield Trust, www.battlefields.org/learn/civil-war/battles/gaines-mill. Accessed 23 Apr. 2023.

Gomez, Kelly. “Winston Memorial Chapel.” Home –, 12 Sept. 2022, theforgottensouth.com/winston-chapel-culpeper-virginia/.

“Jane Chapman Slaughter, Phd in French.” Geni_family_tree, 2 May 2022, www.geni.com/people/Jane-Slaughter-Phd-in-French/6000000175859298080.

Landon, Letitia Elizabeth. 1841. The Poetical Works of Miss Landon. UVA Library Collection, Barcode: X001273869

Stauffer, Andrew M. 2021. Book Traces : Nineteenth-Century Readers and the Future of the Library. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

VMI Archives Historical Rosters: Philip Peyton Slaughter, archivesweb.vmi.edu/rosters/record.php?ID=651. Accessed 23 Apr. 2023.