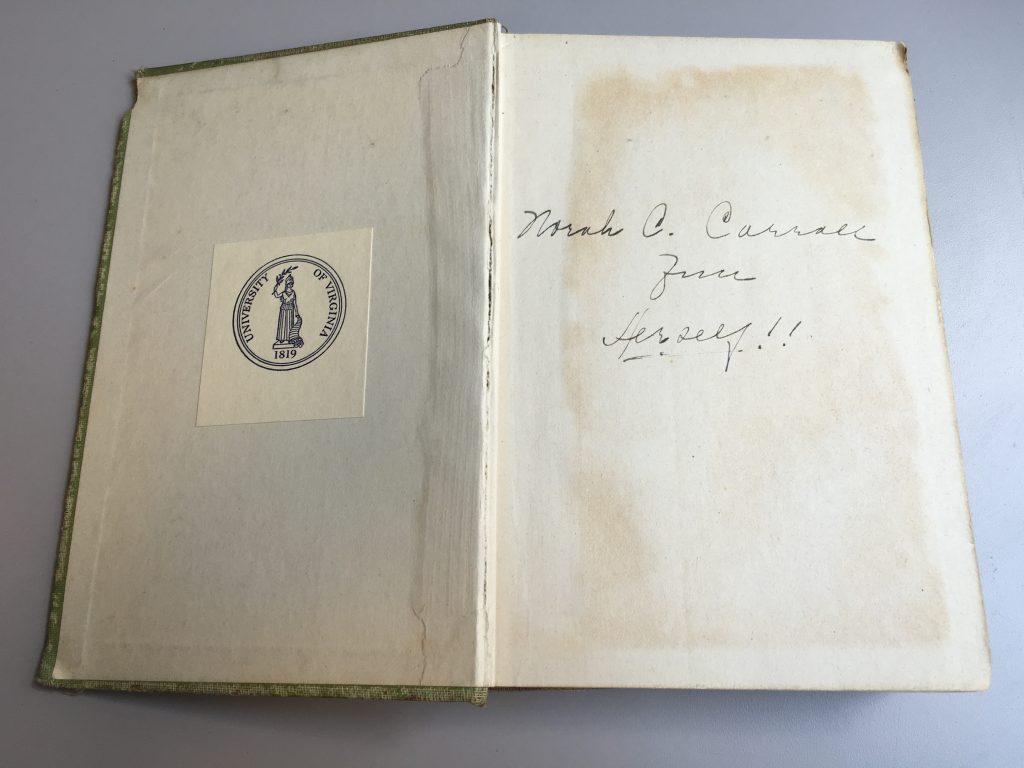

While assessing the latest delivery of books from the Ivy Stacks Storage Facility, I very nearly missed the first Book Find that made me laugh out loud. On the flyleaf of a 1919 copy of Burned Bridges by Bertrand W. Sinclair was what appeared, at first glance, to be a classic early twentieth century gift inscription but ended up being much more humorous.

The book’s apparent owner wrote her name, “Norah C. Carroll,” in neat cursive centered on the page, with a predictable “from” underneath. But then, at a jaunty angle with a quickly scrawled underline and two exclamation points, the gift giver is revealed to be “Herself!!”

My first thought about this intervention was that it was truly something special. During these first few months of my pulling volumes from Alderman’s shelves and sifting through Ivy delivery boxes, I have seen many proud inscriptions of ownership as well as tender gift notes in the front matter of books. At first glance, I was ready to log this example into our Google Form as being just another “Inscription > Gift Inscription,” but then the surprise hit me. The only word I could think of to describe Norah C. Carroll in that moment of discovery came to me in French: this lady, she has panache.

My second thought was that I wished I had thought of this gesture of panache myself and made a mental note to do the same whenever I bought a new book. Essentially, even though I knew absolutely nothing about Ms. Carroll, I already wanted to be her.

This desire only grew when I remembered that this woman was not a twenty-first century inductee into Parks and Recreation‘s “Treat Yo’self” culture of hedonism but instead an assertive female voice writing to us from circa 1919. The layers of her audacity thickened when I found out, via a 1930 United States Federal Census for the city of Charlottesville, that Norah C. Carroll would have been about forty-two years old at the time of her inscription and was ostensibly a housewife (Occupation: “None”) with an eleven-year-old son. My admitted bias to read the gift inscription as a feminist act could even be confirmed by further digging into her biography which, at least to a modern researcher, also suggests that Carroll was a woman who made unique life choices. First, given that her son James P. Carroll was born in 1908, Norah C. Carroll would have been (as far as we know) a first- time mother at age 31. Though it was difficult to find childbirth data for Carroll’s generation specifically, a longitudinal study of childbirth in the United States starting with women born in 1910 confirmed that Carroll’s story of motherhood was just as rare as her gift inscription. The study’s data demonstrated that

[f]or women born in 1910 and 1935, having a first birth after age 30 was relatively rare (less than 10 percent of births) (Kirmeyer and Hamilton 2)

If it was rare even for women born two generations later than Carroll, how anomalous must her story of motherhood have been?

Later in life, we also see Carroll striking out on her own, this time with ramifications beyond the statistical. In 1957, a U.S. City directory for Richmond, Virginia reveals that Carroll had moved away from Charlottesville. Furthermore, there is neither a James P. or Payne J. Carroll listed in the directory. Barring a situation where Carroll was living with a sister or brother listed under her maiden name (which I was not able to find), all signs point to Carroll, then aged 80, striking out on her own to a new, bigger city.

Last, but certainly not least, if we take this inscription out of the narrative of Carroll’s own biography, the inscribed year of 1919 is, of course, symbolic in its own right. Could Carroll have been asserting her own purchasing power in the same year that women of the United States were finally granted the right to assert their political views? The book itself is even called Burned Bridges, which we could choose to read as a metaphor for the year 1919’s departure from pre-suffrage womanhood to a new, enfranchised femininity.

Again, it is very tempting to view Carroll’s biographical details and the year of her inscription through a feminist lens. Yet, circumscribing her defiant act within the broader framework of an ideological movement takes the emphasis off of the profound material evidence we are privileged to behold today from 2016. In light of this, I prefer to view Carroll’s inscription not as a feminist act but instead a radical act of self-indulgence and even self-love that attests to her personal panache as a woman in an era of change.

WORKS CITED

Kirmeyer, Sharon E. and Brady E. Hamilton. “Childbearing Differences Among Three Generations of U.S. Women.” NCHS Data Brief, No. 68, 2011. PDF.

United States. Census Bureau. “Department of Commerce and Labor– Bureau of the Census, Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1930, Population, Charlottesville.” United States Census 1930. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 4 May 1930. Web. 10 November 2016. Ancestry.com.

United States. Census Bureau. “Department of Commerce and Labor– Bureau of the Census, Census of the United States: 1957, Population, Richmond.” United States Census 1957. Washington: U.S. Census Bureau, 4 May 1957. Web. 10 November 2016. Ancestry.com.