Editor’s note: This is a guest post written by Book Traces @ UVA intern Araba Dennis, a double major in Latin American Studies and American Studies who spent part of the fall 2016 semester researching the history of the Alderman Library collections.

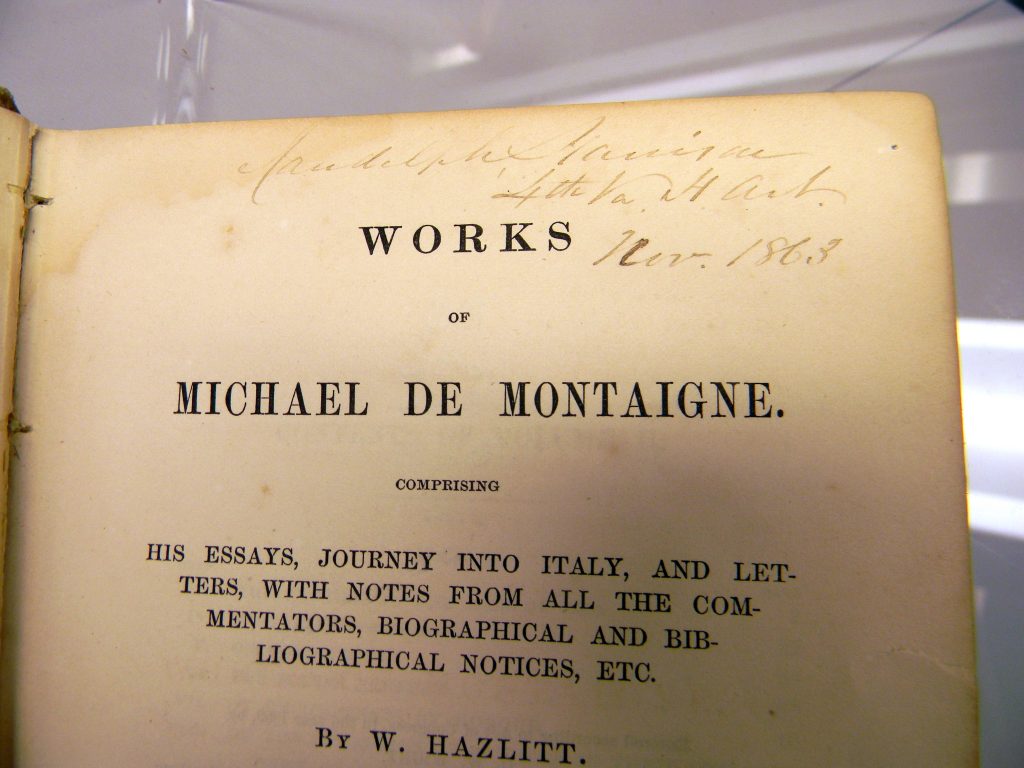

One of the most fascinating aspects of a project such as Book Traces is its ability to uncover the richness of history that exists both in and around UVA. As a student traversing around Grounds for classes and meetings in any given 200-year-old edifice, rarely do I delve deeply into the history of how that edifice, statue, or even a serpentine garden wall came to be. One such example rests in the history of McKim Hall, currently existing as an array of administrative offices for the University of Virginia Health System; this purpose is not terribly far off from its original in 1930, being a dormitory for nursing students.[1] This hall was named after none other than Randolph Harrison McKim, owner of one of Book Traces’ recent finds, an extended copy of Works of Michael de Montaigne with the inscription: ‘4th Virginia H[eavy] Art[illery] Nov. 1863’.

Randolph Harrison McKim was born in Baltimore in 1842, not even two decades shy of the beginning of the American Civil War. A student at the University of Virginia in 1861, McKim was swayed to join Confederate forces after seeing a secession flag waving from the dome of Jefferson’s Rotunda[2]. Witnessing the cheers and nearly explosive Southern pride touted by students and professors alike, that day, McKim decided to join the Confederate army as a member of the 4th Virginia Heavy Artillery directly after his graduation in 1861; he ascended to the position of lieutenant, and soon to chaplain of the entire 2nd Virginia Cavalry.[3]

McKim’s reading habits throughout his life, borne through his love for academia during his time at the University and even more greatly cultivated during his time at war, correlate greatly to his ownership of the Montaigne work; even more so, one can further understand why the University would name a building in McKim’s honor. In his first year as a student, McKim took classes in French, German, moral philosophy, and senior math. Many of his extracurricular readings centered on the new schools of thought developed by Western philosophers. McKim details this with a letter written to his mother on June 20, 1861: “I stand moral philosophy on Tuesday next. To-morrow and next day I am to read two essays in the Moral class,–one on two of Butler’s sermons, one on a chapter in the Analogy”[5].

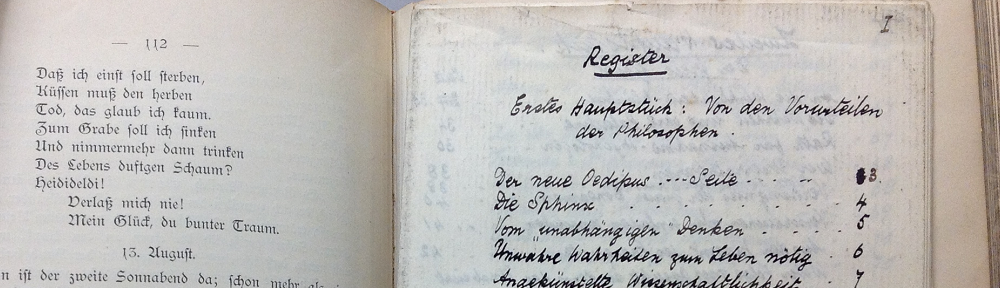

Throughout the war, McKim remained an avid reader, despite having left volumes in his dorm at the University and losing many of his books when the Heavy Artillery would transfer camp. Leading up to 1863 and even beyond, McKim journalled about his enduring passion for reading. In a diary entry after the Battle of Manassas, composed on January 24, 1861, McKim notes:

“I have felt my ignorance lately in listening to men in the mess of greater age and far greater reading and information than myself. In listening to George Williamson, describing the cities, and the manners of foreign countries, and the monuments of art and antiquity in Europe, I have felt a longing to travel, and to learn more of men and things; and I have sighed in contemplating my ignorance of the world of Nature, of literature and of art, and yearned to drink deep of knowledge.”[2]

The loss of the Confederacy was not quite the end of Randolph Harrison McKim’s journey. McKim was ordained as a minister in 1866, and served as a pastor until his death in Washington, DC in 1920. McKim recorded his growing affinity for theology in diary entries and letters to loved ones during the war. For example, on February 4, 1863, McKim described in a journal entry his leading of worship amongst the Heavy Artillery — it is also imperative to note that, immediately following this entry, McKim claimed that, deeper into the war, all of Northern Virginia was swept up in a religious fervor:

“On Saturday evening I again commenced the prayer-meetings. Only a few came, but I felt sure the numbers would increase. The next day I was sent over to Major Snowden’s headquarters as corporal of the guard and was obliged to stay all night. I read the XXVIIth chapter of St. Matthew aloud to the men on guard.” [2]

Ten years before his death, the former Confederate lieutenant published A Soldier’s Recollections: Leaves from the Diary of a Young Confederate, with an Oration on the Motives and Aims of the Soldiers of the South, a personal anthology of the battles McKim fought as a member of the 4th Virginia Heavy Artillery.[5] Additionally, in McKim’s will, he left a sizable portion of his estate to the University of Virginia – some of which included nearly $70,000 for which he requested the construction of a new nurses’ dormitory.

McKim Hall was designed and opened for use in 1930. Coincidentally, this was only a few years before Alderman Library officially opened, simultaneously aggregating collections through donations and books left behind by students; perhaps McKim left the collections as part of the estate he bestowed upon the University. One way or another, Book Traces’ ability to uncover this little piece of a larger puzzle gets us closer to an understanding of history, of people, and of the University of Virginia as a whole.

[1] Virginia, University of. McKim Hall, School of Medicine Administration. n.d. 24 October 2016 <http://www.virginia.edu/webmap/popPages/120-MckimHall.html>.

[2] McKim, Randolph Harrison. A Soldier’s Recollections. New York: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1910.

[3] Confederate Vets. n.d. 26 October 2016 <http://www.confederatevets.com/documents/mckim_dc_cv_09_20_ob.shtml>.

[4] Internet Archive. Works of Michael de Montaigne; comprising his essays, journey into Italy, and letters, with notes from all the commentators, biographical and bibliographical notices, etc . 1864. 26 October 2016 <https://archive.org/details/worksofmontaign03montuoft>.

[5] Confederate Vets. n.d. 26 October 2016 <http://www.confederatevets.com/documents/mckim_dc_cv_09_20_ob.shtml>.a