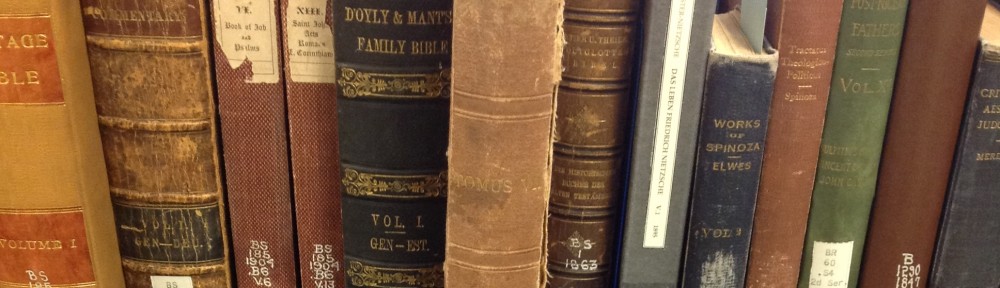

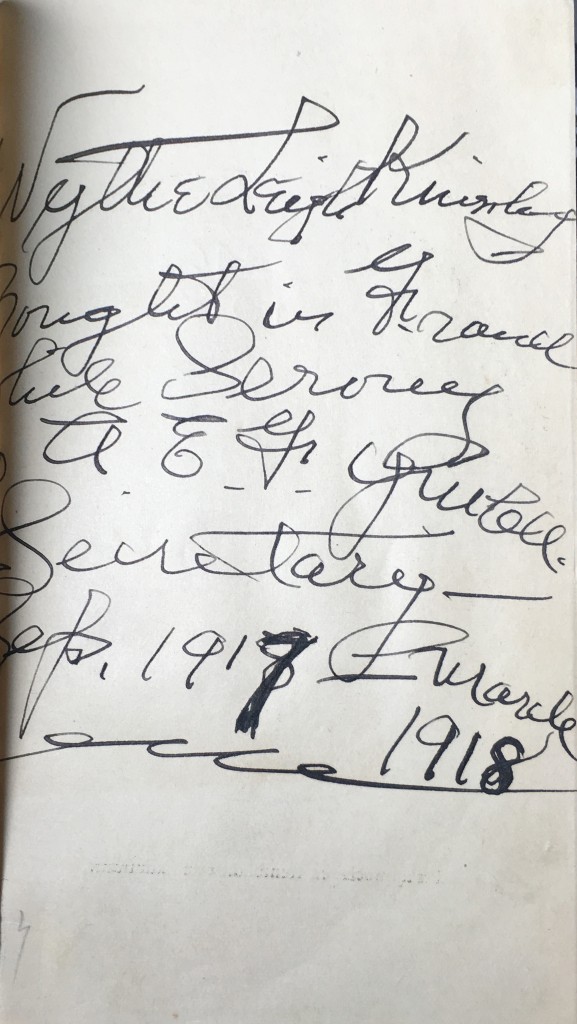

On the page preceding the cover page of our 1913 edition of Choix de Contes de Fées (“Selected Fairytales”) is an inscription specifying the book’s original buyer as well as the location and date of its purchase:

The inscription reads:

Wythe Leigh Kinsolving

Bought in France

While serving

as A.E.G. Purcell [?]

Secretary

Sept. 1917- March 1918

It is rare to get such a detailed context for the purchase of a book, but either Kinsolving himself or an astute librarian had a keen eye for this particular item’s posterity: the temporal context, when cross-referenced with Kinsolving’s biographical details, reveals that this book was purchased while Kinsolving was abroad during the first World War.

Originally, when the Book Traces team found the inscription, the word “serving” led us to believe that Kinsolving served in the armed forces during the War. We were perhaps misled because the Book Traces project (at UVa and beyond) has indentified two additional traces from American Civil War soldiers who memorialized their stints in military service.

This was, however, not the case with Kinsolving. A fervent pacifist and a devout Christian, Wythe Leigh Kinsolving primarily identified as a Reverend and a religious journalist. He was born in 1878 in Halifax, Virginia, and received his formative education in other parts of the state: he earned a Master’s Degree at the University of Virginia in 1902 and a B.D. degree at the Virginia Theological Seminary in Alexandria in 1906. He then married and served as a minister in Maryland, Missouri, and Tennessee. When World War I broke out in Europe, Kinsolving chomped at the bit to be allowed to serve as an official minister. Finding that all of those positions were filled, he applied to work at the Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) in Paris.

It is very appropriate that Kinsolving purchased a book of fairytales while in Paris because his experiences there were very rosy indeed. Knowing what we now know about the new form of warfare’s traumatic effects on the psyche of soldiers, it may be hard for us as modern readers to stomach some of Kinsolving’s shockingly out-ot-touch descriptions of the war. In his memoir of his time in Paris, From the Anvil of War (1919), he compiles his literary output from from 1914 to 1918: his correspondence, his journalism, and his attempts at poetry that, from a technical standpoint, are thoroughly mediocre.

In order to get a sense of just how apropos Kinsolving’s purchase of a fairytale book is, it is important to get an impression of the shallowness and remove of Kinsolving’s poetry. First, he greatly minimizes the terror of the trenches and of the Front. In a poem titled “They Went to War with a Song,” he declares,

“Did they lose their grip in the trench in the long dread hours?

Nay! They went to the war with a choral strong and gay;

They fought to the end with a purpose glorified.” (9)

Though he acknowledges soldiers’ endurance and praises their morale, his depiction of a war full of song is at best idealistic and at worst deeply offensive. Second, he appears to inflate his own experiences at the Front, which he only, based on his correspondence with various newspapers, visited for brief periods a handful of times. In the highly repetitive “Tribute to France!” he paints a vignette that makes it seem like he lived through the firefights and personally nursed the wounded (when, meanwhile, he laid out snacks at mess halls on his busiest days):

“My heart hath been in France!

These many days my heart hath been in France.

I’ve lived amid the storming crash of guns!

…

I’ve knelt beside the wounded soldiers there!

I’ve offered God a fervent prayer

For France, brave France.

Strong, noble, gallant France!” (5)

Of course we must accord Kinsolving some poetic license and room for hyperbole in his verse, but his inclusion of such a poem in his personal memoir smacks of an exaggerated, romanticized view of his minimal participation in the war. Indeed, this tendency to romanticize carries throughout the volume, for he third indulges in exoticism of French women in a poem entitled “Tricolor Stars and Stripes,” where he describes a romance between a rookie American colonel and French girl:

“She was encountered in a Bordeaux ‘diner’,

Daintily lunching with her own ‘naman’ [sic],

He, dapper, gay, just off an ocean liner,

Caught first glimpse of her and saw her yawn.

Yawns can be pretty if red lips are parted,

And half-closed eyes are seen to shine,

If from their azure depths a glance just started

Falls ere it reaches you with light divine!

Then, if a dainty purse should fall, just gliding

Out of lap of velvet to the floor

What would you do, monsieur, now be confiding,

Would you not haste the trinket to restore?” (4)

Taken in conjunction with the aformentioned “Tribute to France” and testimonies in his correspondence of French soldiers eagerly awaiting American troops’ arrival, it seems as if Kinsolving is not only exoticizing the beauty of French women but also casting strapping American G.I.s as the savior of the “dainty” France.

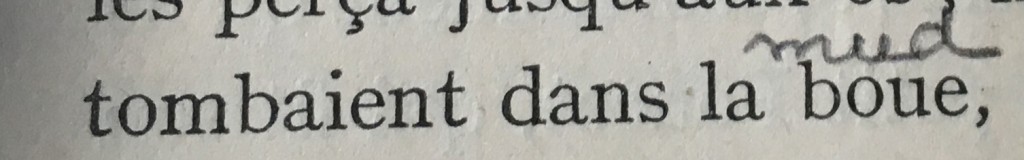

Returning to the book of fairytales, it is not difficult to see that our author has also overplayed his knowledge of the French language. Though he makes myriad mentions of instances in which he spoke in French to Frenchmen and indeed boasts that “French people tell me they understand me perfectly” (16), traces in the volume of fairytales, which I assume to be written in the hand of the book’s original owner (albeit probably a different hand than that of the inscription despite its loopy cursive) betray a certain lack of familiarity with the language.

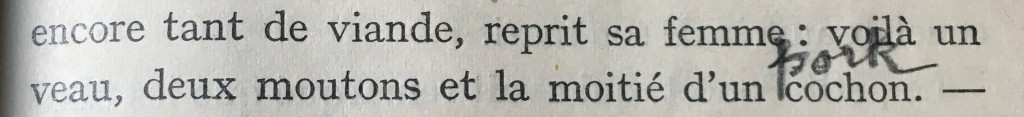

The story of “Le Petit Poucet” (“Tom Thumb”) is filled with cursive writing in English that attempts to translate the French word below it. While some of the translated words are indeed low-frequency, non-cognate vocabulary words like “escabelle” (“stool”), others are simple, like the word cochon, meaning “pig” or, when eaten, “pork”

Translation “…there is still more meat, his wife replied: here there is veal, two mutton chops, and half a side of pork” (77)

and — ironically enough for someone who vaunts that he has visited the trenches and spoken with French soldiers there — la boue, meaning “mud,” and crotté, meaning “dirty” or “caked in dirt”

Translation: “…you are quite hungry; and you, Little Pierre, look how dirty you are! Come here and let me clean you.” (73)

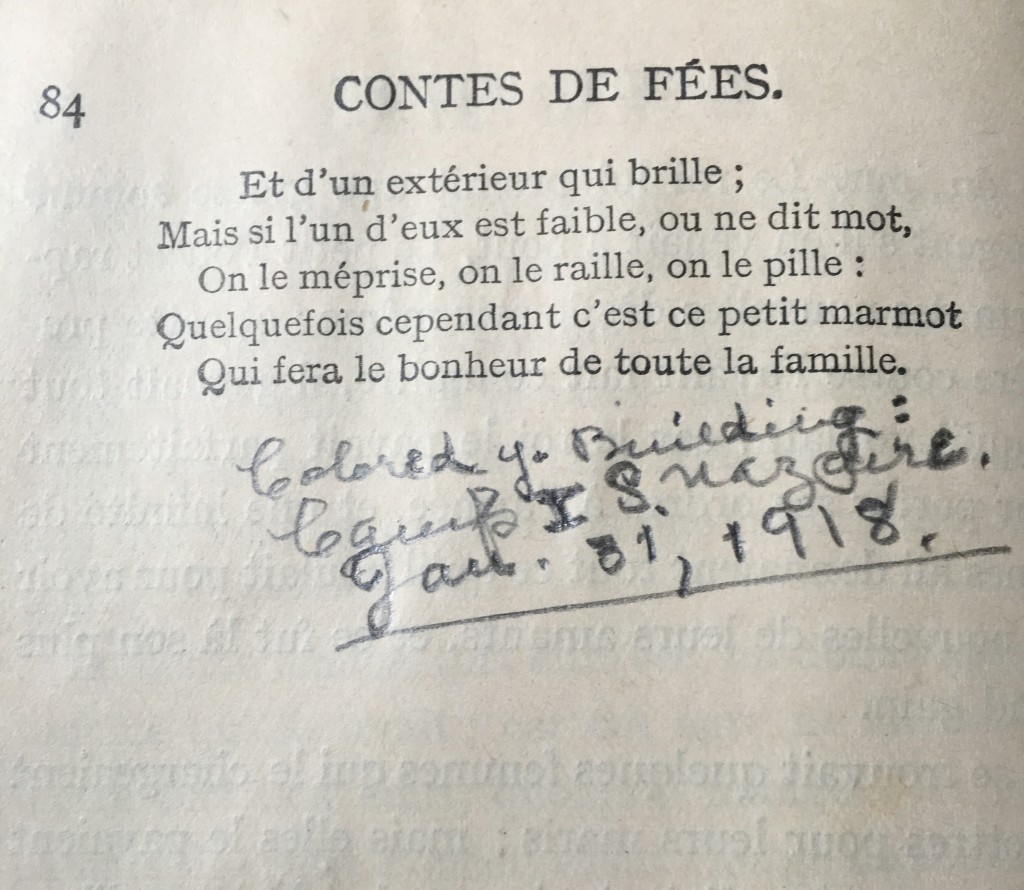

Despite his faux pas, he does afford us one authentic vision into the tableau of his travels abroad. Scrawled at the end of the aforementioned “Tom Thumb” story is an address. This address appears to have been written quickly and therefore it is somewhat hard to read the scrawl. Using the context, I believe the address to read:

Translation of the excerpt of the story’s moral: “And the exterior shined brightly/ But if one is weak and speechless/ One will be despised, teased, and robbed:/ Sometimes it is the small brat/ Who will save the whole family.” (84)

Colored y. building:

le camp [?] I S. Nazaire

Jan. 31, 1918

This intervention follows the trend established in the front matter: Kinsolving (or at least those conscious of his legacy) liked to add geographic data to literature. Just as the inscription at the beginning tells us that Kinsolving bought the book in France, this address at the end of “Tom Thumb” seems to suggest that it was in this location that Kinsolving puzzled his way through the French story, translating the unfamiliar words. If Kinsolving was merely using the page as a spare sheet of paper to commit an address to memory, it is unlikely that the address would be centered on the page and underlined; this alignment and demarcation insinuates a connection between the story and the handwriting.

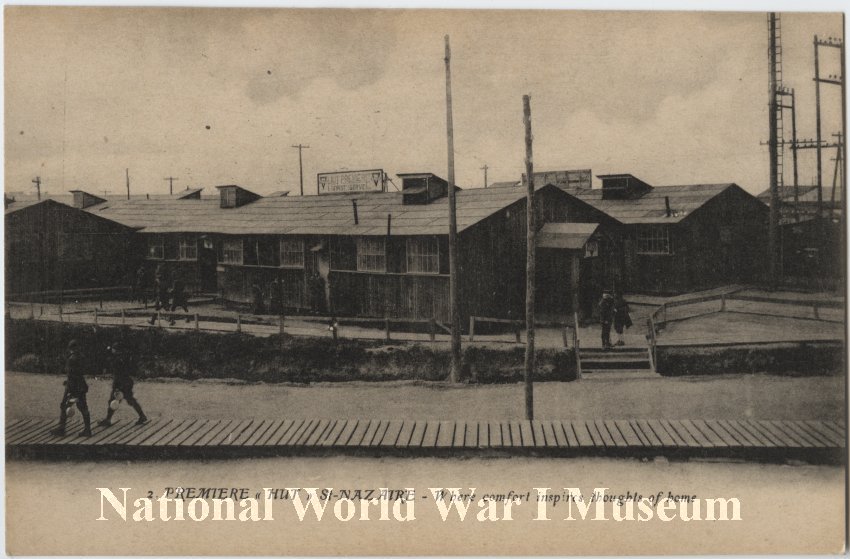

Indeed, Kinsolving’s memoir tells us that he did visit the shipyard at Saint-Nazaire on France’s Northern Atlantic coastline, and my research revealed that there was a Y.M.C.A. compound in the town, called “Camp No. 1,” which may explain Kinsolving’s “Colored y. [as in “the Y”] building.” Whether any of the Y.M.C.A. facilities were “colored” in any way remains difficult to say, since photographic remnants are in sepia tones and I could not find any documentation referring to the physical traits of the buildings. However, the captions printed on this card in the archives of The National WWI Museum and Memorial does speak to the warmth of this site:

Front of the card:

Premiere «Hut » St-Nazaire – Where comfort inspires thoughts of home”Back of the card:

A building in which tens of thousands of doughboys received comfort and refreshment during the trying days of the War and in the restless anxious period of home-going. Approximately 2,000,000 letters were written by the soldiers here.

It is fitting that this same site where Kinsolving engaged with foreign-language literature was also the locus of literary output in the form of soldiers’ epistolary writing. It may even have been this place-based incentive for writing that propelled Kinsolving to pair his own writing and his literary acquisitions with geographic data. We have also seen this tendency to geographically situate recollections of war with our other Book Finds from the American Civil War: Private Robert E. Jones wrote in a book of William Cowper’s poems that he was “on the line” at Richmond less than a month before his death, and a writer identified only as James R. reflected in a letter to Thomas Randolph Price upon his service twenty years prior in “dear Richmond.” Though Kinsolving shares a tendency to root his reading and observations in time and space with these veterans, they are notably much less flowery and even curt in their recollections of the war; these locations are their only definitive traces. Even as these Confederate soldiers express some nostalgia for Richmond in their writing, they steer clear of Kinsolving’s sensationalist tendencies.

Indeed, Kinsolving seems to use his geographic data to a dramatic end rather than merely noting a location for posterity. The annotation of “Tom Thumb” specifically becomes more meaningful with this geographic context: soldiers who felt small fighting an impossible enemy in the trenches could once again find dignity and purpose at Camp No. 1 just as the main character of the fairytale learns to respect himself in spite of his shortcomings after singlehandedly defeating a fearsome ogre.

Though Kinsolving presents us with a view of World War I through the rose-colored glasses of an eager reverend on his first extended trips abroad in the land where Western fairytales were written, it is clear that he and his colleagues of the Y.M.C.A. at least afforded “comfort and refreshment” to war-weary men. Perhaps even his optimistic assessments of war, which border on insensitive in a retrospective reading, provided comfort and escapism via his unwavering idealism in the moments when it mattered most.

WORKS CITED

“2002.3.22.” Photographic Print. The National WWI Museum and Memorial. Web. 16 May 2016.

Kinsolving, Wythe Leigh. From the Anvil of War. Winchester, TN: Southern Printing and Publishing Co., 1919. Web. HathiTrust Digital Library. 26 May 2016.

Perrault, Mme d’Aulnoym Mme Leprince de Beaumont, and Hégésippe Moreau. Choix de Contes de Fées. Paris: Nelson, Éditeurs, 1913. Print.

Rathjen, Jamie. “Book Find: Cowper After the Storm.” Book Traces @ UVa. University of Virginia Library. Web. 27 May 2016. <booktraces.library.virginia.edu>.

Stauffer, Andrew. “Henoch Arden.” Book Traces. Web. 27 May 2016. <booktraces.org>.

Stowe’s Clerical Directory of the American Church 1920-21 (biographial listing of Episcopal clergy). Minneapolis: Andrew David Stowe, 1920. Web. 26 May 2016.