Editor’s note: this post was researched and written by Book Traces @ UVA project assistant Nitisha Potti, with editing by me (Kristin Jensen).

One of the greatest perks of working with Book Traces @ UVA is that you come across these very fascinating and interesting interventions in various books, some of which are very puzzling like when you find some doodles drawn across the book on various pages, some of which may be related to the text and some may not. Some of the books have poems written in them, which may or may not be original. But the most exciting for me are those which have remarkable interventions spanning across various decades, yet have so much in common with the text that they could be easily mistaken to be written by the author himself or herself.

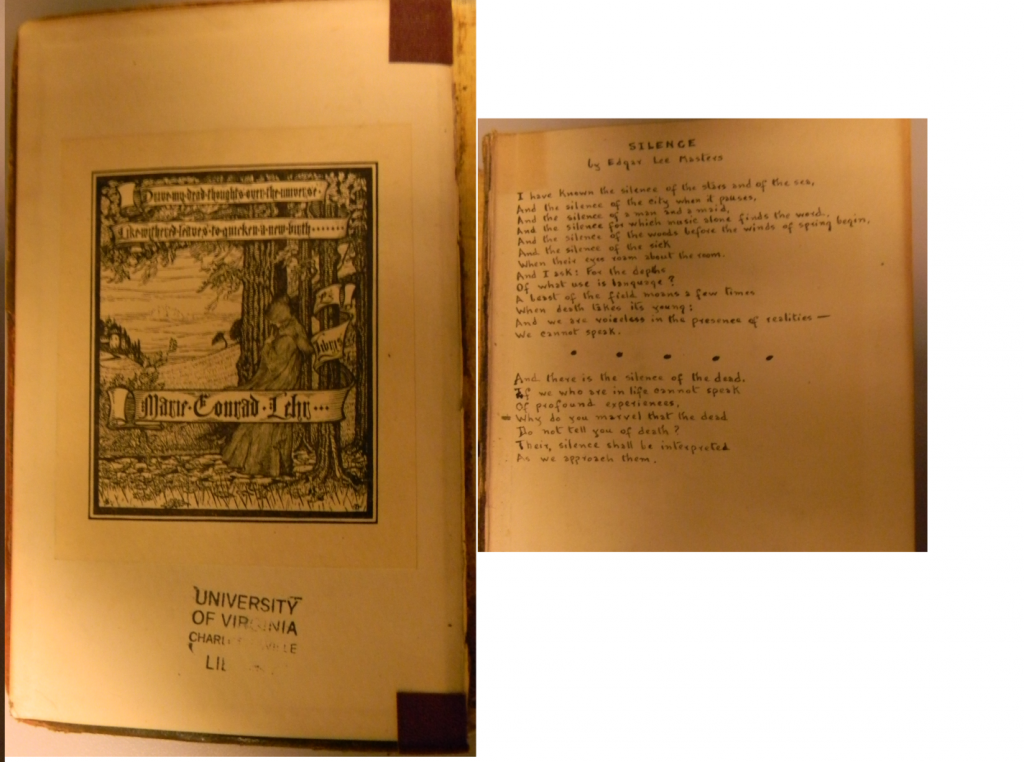

One such intervention which caught my eye appears in the UVA Library’s copy of The Treasure of the Humble written by Maurice Maeterlinck and translated by Alfred Sutro, published in 1900. It is a poem titled Silence written by Edgar Lee Masters and copied by hand onto the free endpaper by an anonymous owner of the book. Now, the owner might have possessed the book in 1946 or later, since Silence was written in 1946. Book Traces @ UVA usually deals with interventions made before 1923, but this book has one more intervention which piqued my interest to write about this book. It has a very peculiar bookplate with the name of Marie Conrad Lehr on it. Mrs. Lehr lived from 1884-1921 (according to various online sources), a period which falls under the Book Traces @ UVA research era. This book is a classic example of what is called a “mixed scene” here at the Book Traces project, i.e. a book with interventions ranging over various times periods by different people.

As the interventions found in this book are very atypical I thought that the content of this blogpost should also be different from the previous blogposts where I tried to reason or dig as to why those interventions ended up in those books or why did the people involved make those interventions in those books. Therefore, for this blogpost I decided to find a link between the various people involved with these interventions based on the thoughts reflected from the text of the book and the interventions.

As I read the introduction written by A. B. Walkey for this book The Treasure of the Humble, I get the sense of the book being written in a very spiritual manner of which you become sure when you read a line about the author from the introduction: “This volume presents him in a new character of a philosopher and an aesthetician.” Mr. Walkey calls Mr. Maeterlinck a Neo-Platonist in the introduction. The same can be seen from the first chapter Silence in this book. The author is found advocating silence over words and emphasizing the importance and strength of silence during and after the life of a human being: “let silence have had its instant of activity, and it will never efface itself; and indeed the true life, the only life that leaves a trace behind , is made up of silence alone.” Since the author strongly believes that a life is made up of silences more than anything else and you can find these silences in every part of life, I was astonished to see the poem of Edgar Lee Masters on the front page which propagates an idea similar to the idea put forth in the first chapter of the book.

The person who inscribed this poem in the book only wrote the first and the last stanzas of the poem, perhaps because those are the only two stanzas that relate so closely with the text in the book. In the first stanza the poet writes, “And I ask: for the depths, of what use is language?” To give more of a context: the poet starts off by saying that he has seen the silence of the stars, the seas, the city when it pauses, the woods before spring and so on and after seeing all these silences he wonders what is the use of language, of words more so when we are voiceless in the face of realities. When you read the poem after the text or vice-versa it doesn’t feel that they have been by different people from written in two different eras.

Opposite the poem on the free endpaper of The Treasure of the Humble was the bookplate that belonged to Marie Conrad Lehr, which was stuck behind the front cover, and on it were these words taken from a poem “Ode to the West Wind” written by Percy Bysshe Shelley:

“Drive my dead thoughts over the universe

Like withered leaves to quicken a new birth”

Marie Conrad Lehr was a direct descendent of Martha Washington on her paternal side. According to many online sources, Mrs. Lehr and her husband did a lot of social work and donated to many social causes and also after her death she gave away many of her personal belongings and her art collection to museums and Mount Vernon’s Ladies Association. It seems apt for a person who gave back to the society so often during her life and also after it to have chosen such words for her bookplate. Percy Bysshe Shelley asks the wind to carry his thoughts through time like it does with the dead leaves, which is symbolic of the fact that only our thoughts that survive even after our body perishes, which is so much in keeping with the tone of this book The Treasure of the Humble.

The fact that Marie Conrad Lehr and the anonymous owner of the book who wrote the poem Silence on the flyleaf both chose somebody else’s words to inscribe in the book shows how strongly these words resonated with them. When they came across this book that conveyed the same message that Silence and Ode to the West Wind conveyed they felt the urge to have these two literary works in the book. The most amazing part that reinforces what the text and both the poems are trying to tell, i.e. about the power of silence and that it is the thought which prevails even after the soul leaves the body, is that these interventions were made by two different people in two different decades in the same book. Thus, the thought that links the author of the book, the earlier owner of the book, and the later owner who wrote down the poem in the book is the belief that a noble thought is what prevails even after death and the silence that follows it.

Works cited:

Maeterlinck, Maurice . The Treasure of the Humble.

“Montmorenci–Marie Conrad Lehr.” worthy2be.wordpress.com/2012/06/17/montmorencimarie-conrad-lehr/.

Masters, Edgar Lee. “Silence.” www.bartleby.com/104/43.html.

“Percy Shelley: Poems.” www.gradesaver.com/percy-shelley-poems/study-guide/summary-ode-to-the-west-wind.